Once again, more than two years have passed since I last time I wrote one of these posts. Check out the first of these from back in 2007 here and my update from 2009 here. All the usual caveats apply: favorite films are not best films and the date that this post is made has nothing to do with the release dates of the films featured herein. Always consider these lists to be an addendum to previous lists, not a replacement. And since everyone hates reading long prefaces, let’s get right down to it and just refer to the previous posts if you’re still confused.

Spoilers may follow so consider yourself warned.

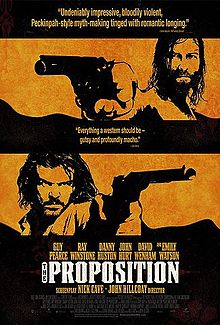

The Proposition

The Proposition

Good movies can be good for many different reasons. Sometimes the actors steal the show, other times the plot is so arresting that you barely notice who’s onscreen. In The Proposition, the real star is the Australian outback in which the film was shot. It’s a gorgeous landscape, but gorgeous in the sense that even an uncompromising and pitiless vision of hell can be aesthetically pleasing. The rays of the sun cast alien colors and shadows upon the land, the sky weighs so heavily that we almost flinch from it. It’s a wonder that anything can live in such an inhospitable desert.

Unsurprisingly, a harsh land breeds harsh men. There is no morality in this film. The struggle here is between the more primal forces of order versus chaos. The sheriff-like character, the ostensible hero, boldly declares near the beginning of the film, “I will civilize this land.” Yet we all know, from the buzzing of the omnipresent flies, the cured leather faces of the men he must deal with, the indifference of the native Aborigines, that this is an untamable land. Nothing exemplifies this futility more than the sheriff’s wife, who gamely attempts to recreate a patch of England in wild Australia, complete with rose bushes and afternoon tea in proper teacups and saucers.

Screenwriter Nick Cave is a musician first and a writer second, and this film’s eerie and memorable soundtrack which fills more spaces than the sparse dialogue, is the perfect accompaniment to a view of a historical Australia such as we’ve never seen it before.

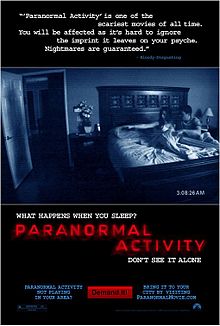

Paranormal Activity

Paranormal Activity

Some successful horror films, Let the Right One In for example, induced fear not by showing physical violence but by portraying the horror of a situation or the evil in men’s hearts. Paranormal Activity, by contrast, is a study in simplicity. Here, the root of the horror is the old-fashioned kind, of evil, otherworldly things doing horrible violence to you. But in an age of inexpensive CGI, first-time director Oren Peli understood that no monsters can be scarier than the ones you create yourself in your own imagination.

Hence this film strikes fear not by showing horror onscreen, by but showing you next to nothing and allowing your imagination to fill in the blanks. Many minutes go by with no movement at all save the ticking of the time counter, yet we are riveted all the same. With so much tension hanging in the air, even the merest rippling of a blanket will leave you gripping your armrest with white knuckles.

The ordinariness of the house and blandness of the couple only add to the horror. We may be inured to all manner of fantastic creatures if we think it lives on the silver screen, but when we believe that they can invade our very own homes while we sleep, even the most battle-hardened of film-goers will be screaming in terror.

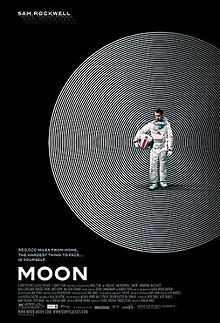

Moon

Moon

If you’ve never seen Moon and I were to tell you that this is a film which consists of nothing more than actor Sam Rockwell talking to himself, you might be forgiven for thinking that this is arthouse fare of the most pretentious kind. In fact, while Moon is unashamedly intelligent, it is never boring and surprisingly approachable. This is an intense, implacably cold, examination of loneliness and the psychological trials that must inevitably befall humans sent to work alone in far-off locations.

What I love about this film is that it never plays the audience falsely. Lesser directors might opt for obfuscation between what’s real and what’s merely in the mind, but Duncan Jones plays it straight. You’re confused when Rockwell’s character is confused but you’re allowed to share in the insights of the character at the same time that he earns them. Film geeks will also enjoy the allusions to and clever subversion of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

One nitpick I have is that it gets important bits of science wrong, which is disappointing given how well-thought out everything else is. How come gravity is light outside but seemingly normal inside the base? How can Rockwell’s character view the Earth if he’s supposedly on the far side of the Moon? But these are concessions to budgetary constraints and cinematographic beauty that don’t prevent Moon from being one of the finest hard sci-fi films ever made.

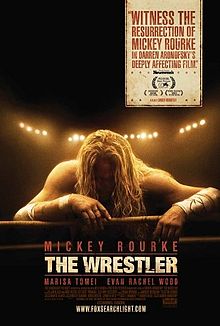

The Wrestler

The Wrestler

As a rule, I detest sports films because they tend to repeat the mind-numbing motivational pap of the self-help industry: the importance of teamwork, the power of determination to overcome all obstacles and transformational improvement all within the time that it takes to go through a training montage. The Wrestler is a great film because it is the polar opposite of that view: to truly be the best of the best, you essentially have to sacrifice everything else, to the point where your art is the only thing you have left.

Through a combination of impressive physical acting on the part of Mickey Rourke and an exacting eye for realistic behind-the-scenes details of the pro-wrestling world, the film evokes heartfelt sympathy for the title character. You know he’s destroying himself but you also know that this is the only path that is right for him and there is nothing that anyone can do about it.

It is impossible to comment on this film without mentioning its companion piece, Black Swan, also directed by Darren Aronofsky. Of the two, Black Swan is perhaps richer and more artistically beautiful, but The Wrestler evokes emotions that feel more grounded in reality and therefore feels more genuine.

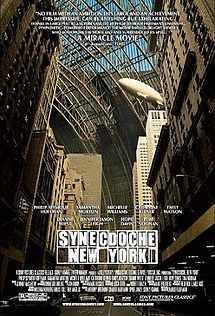

Synecdoche: New York

Synecdoche: New York

The least approachable of the films in this list earns this status by also having the highest density of ideas. The premise begins humbly enough: a theater director embarks on a project to create a play while dealing with his personal problems. At some point in the film, we step out of reality though it’s impossible to say exactly when that is. Why does the staging of the play go on and on and on, growing bigger and bigger until it seemingly becomes the entire world? At the same time, why does his estranged wife’s paintings become smaller and smaller until they can only be seen with a microscope? Why does it seem that over time his characters develop minds of their own and become more real than himself? Did the director himself even exist in the first place?

The film plays tricks with time and space and is full of meta-referential allusions. All the better to explore the subject that is clearly of most interest to director and writer Charlie Kaufman, the nature of the human mind. This is a film that I can’t claim I’ve fully understood but its intelligence and soaring ambition are apparent enough. If you were impressed by the multiple levels of dreams in Inception, Synecdoche, New York will blow you away, unless it makes you run away in confusion first.