My wife and I are currently deep into the fourth season of The Wire, one of the most highly recommended series on QT3. In fact, a number of noted critics from among many others TIME, Entertainment Weekly and The Guardian, have called it the greatest television show ever made. The Guardian in particular loved it so much it ran a blog devoted to it with an update after every episode and for a while made the first episode of the first season available for download on their own website. Yet this was a series that struggled to find an audience when it was on the air and that has conspicuously failed to win any Emmys.

It’s not hard to see why. While the series is presented as a crime drama and the first season certainly does its best to trick you into thinking that it is one, the show is really a wide-ranging window into the world of Baltimore and the people who must live in it. As such, it’s uncompromisingly realistic, ambitious and deep. True to the demographics of the city, the cast is principally black. All characters use authentic dialogue, so it takes a while for the uninitiated viewer to get to grips with what they’re talking about. The street-level gangsters talk in slang. The police and their legal support staff use technical jargon.

The show is also depressingly bleak. It’s not so much that it presents its characters as flawed individuals. Even worse, it shows the viewer how the institutions and organizations of the city set the people of Baltimore up to fail, warping and grinding up even the noblest of people. It doesn’t matter how good your intentions are or how hard you try, the show seems to say, bureaucracy and perverse incentives will doom even the best efforts to improve life in the city every time, and things go on, just as they always have.

One particular scene stands out for me. The series sets up William Rawls, a senior police officer, to be every inch the evil supervisor who regularly stymies good police work. vengefully punishes subordinates who cross him and eagerly fudges crime statistics to appease his political masters. Yet when another officer is shot in the line of duty, he rallies his troops and is shown to be surprisingly sympathetic. The message is clear: it’s nothing personal, it’s just the system that’s fucked up. Don’t look for happy endings or cliched tropes in this series. That makes its plots uncommonly potent but also makes it a show that you need to psych yourself up to watch.

So far, we’ve watched the series cover the detailed workings of both a specialized police investigative unit as well as an established and competent drug-dealing gang in the first season. In the second season, we’ve seen the long-running problems of unemployment and poverty among the mainly white dockworkers of the city, standing in for the wider blue-collar community whose population is inexorably dwindling as whole industries shut down. The third season covers City Hall and looks at how the police are forced to dance to the whims of the politicians and how the hopeless war on drugs makes it nearly impossible to do any actual crime-fighting. The fourth season switches focus on the public schools of the inner city and shows the inevitable path into crime that so many black children end up taking.

Watching the series in 2010, I’m stunned by how accurate and even prescient the series turned out to be. For example, there’s an obvious parallel between the Hamsterdam of the series and California’s attempt to legalize the sale of marijuana via Proposition 19 earlier this year. The heavy-handed and panicky response to it by officialdom when its discovered in the show perfectly mirrors the Obama administration’s no-holds-barred stance against Proposition 19 with its insistence that the federal government would treat marijuana sales as being illegal regardless of which way California voters went. It’s no wonder that so many universities in the US use The Wire as part of their political science and social studies courses.

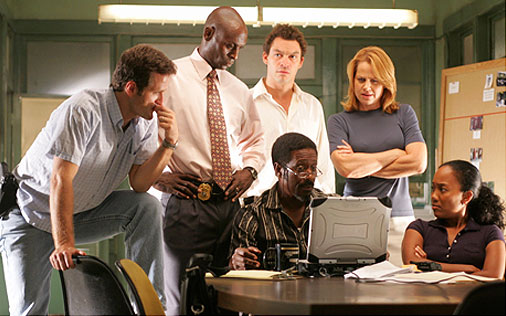

The authenticity of the plot is only one reason why the series is such good entertainment. It’s also incredibly dense, covering many separate plotlines, some of which are only loosely interconnected, and making good use of a very large cast. The acting quality can be a bit uneven but the overall effect can’t be faulted. I’m particularly shocked at how they managed to find so many good child actors for the fourth season. I guess part of the reason is that in many cases they resorted to using non-professionals, coaxing the real-life counterparts of many of the show’s characters to basically play themselves.

A number of scenes are simply sublime. One personal favorite of mine is when two detectives, who have obviously known and worked with each other for a long time, work the scene of a murder without needing to say a single word. They arrive, they cast their critical eyes on the surroundings, pull out tape to make measurements, gesture pointedly to each other and form a conclusion of what actually happened, all in complete silence, much to the bewilderment of a confused civilian onlooker. In another scene, the baddest ass character on the show, who also happens to be gay, strolls casually through the streets in his pyjamas, and still manages to scare the crap out of everyone who sees him.

A while ago, I wrote that Lost was amazing in that it brought theatre-quality cinematography to television. I’d say that The Wire is similar in that once upon a time you’d only expect to see material and plots of this level of quality and intelligence on the silver screen. As a number of commenters have pointed out, including the Freakonomics blog, thanks to HBO, the pendulum has now swung the other way. Where people used to think of television as cheap and disposable entertainment and the cinema was where the real artists did their serious work, the opposite is beginning to be true, at least for Hollywood. This is purely due to the economics of the different businesses rather than deliberate design but it’s certainly heartening to know that the creative space exists for something as good and innovative as The Wire.