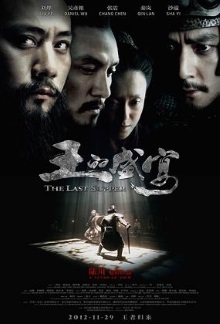

One thing’s for sure about this Chinese film, its English title is appalling. Whoever coined it must either have been unaware of the Biblical connotations of this term or believed that it could be meaningfully appropriated for the historical events which are the subject of this film. Either way, it is a mistake made especially egregious because a straightforward Feast at Hong Gate would have been both simpler and better. Fortunately, this is pretty much the worst thing I have to say about this movie because everything else is utterly fantastic.

This one came to my attention when I complained about how awful City of Life and Death is to my cinephile friend. He suggested that I check this out since it’s by the same director Lu Chuan. Indeed, The Last Supper is so good that it’s hard to believe that it was made by the same person. It does require some knowledge of the history of the period to fully appreciate. I was fortunate in this regard as my wife was on hand to deliver the appropriate background detail.

It is set during and after the fall of the Qin empire and is centered specifically over what actually transpired during the Feast at Hong Gate. There the leaders of the rebellion Liu Bang and Xiang Yu meet. Liu Bang has just taken the Qin capital of Xianyang but Xiang Yu has military superiority and is acknowledged as the supreme commander. By all rights, Xiang Yu should take the opportunity to eliminate a future rival yet Liu Bang not only walks away unscathed but lives on to become emperor and found the Han dynasty. Why?

One of the most admirable things about this film is its sense of restraint. We all know how much makers of Chinese historical films love to show vast hordes of soldiers and the near-super heroic valor of the heroes of the era. Yet despite what looks like a respectable budget and ample source material to draw from, there is almost no fighting to speak of here. It’s just not what this film is about. Even during the martial arts demonstration at the feast, the director shies away from flashy moves. Instead, the warriors move slowly and stylistically, conveying menace in each deliberate movement. I’d imagine that this would be a much more accurate portrayal of the actual martial arts demonstrations of that era. By disdaining showiness, it makes the film feel grounded and real.

One might then be tempted to conclude that this is a film about political intrigue. Granted, Machiavelli would be proud of the cynical and ruthless maneuverings shown here both to gain power and to hold onto it. But that’s not really what this film is about either. Instead it is really a character study of Liu Bang. It strives to portray how he is a man haunted by paranoia and insecurity even more than a decade after he has ascended to the throne. This is a man who knows in his heart of hearts that Xiang Yu is in every way his superior: a more valiant warrior, born of noble stock, admired by all heroes, loved by the most beautiful of women, magnanimous in victory, wise and selfless. Yet he prevailed in the end and not Xiang Yu and it troubles him to no end that he does not truly understand why.

A great moment is when Liu Bang and his troops enter the palace, having arrived before Xiang Yu. They discover the records room which apparently holds information on every citizen of the empire on bamboo scrolls. Naturally Liu Bang is curious about what is written on his own scroll. It arrives with the announcement “Liu Bang of Pei County” and goes on to detail his date of birth, his parents, his siblings, their professions and so forth. The point here is to emphasize that he is just a commoner, an ordinary man out of countless others. Even as an old man in his twilight years, he never stops hearing the refrains of “Liu Bang of Pei County” echo throughout the palace, constantly reminding him of his inadequacy.

The film boasts high production values, a sure director’s hand, solid acting and very impressive make-up work. It’s hard to believe that Liu Ye who plays Liu Bang is only in his mid-30s. My major disappointment is that the empress Lü Zhi is portrayed as a stereotypical evil dowager, which makes her a very uninteresting character. Furthermore, the most recognizable actor here, Daniel Wu, despite an obvious effort to bulk up, doesn’t really have the physique to pull off the legendary Xiang Yu.

What especially intrigues me about this film is the audacity that it takes to portray the founder of the Han dynasty in such a negative light. Here, he is clearly a liar, a coward and is completely without honor. Yet one of the film’s morals seems to be that such cunning and moral adaptability, to put a more positive spin on it, may well be what was needed to forge a dynasty that would last over 400 years. Xiang Yu’s unyielding moral principles on the other hand, brought him nothing but an early death. Compare this to how City of Life and Death might as well have been official Communist Party propaganda.

During the final minutes of The Last Supper, one particular scene made me realize that the whole thing is consciously patterned after Citizen Kane, right down to having a Rosebud moment. To me, this is proof that Lu Chuan is a director who knows his stuff and I am forced to retract what I wrote about his lack of basic competence. Cribbing from one of the greatest films of all time is no sin and I find it refreshing that a Chinese director would think to do so. As far as I’m concerned, The Last Supper isn’t just a good movie. It’s a great movie.