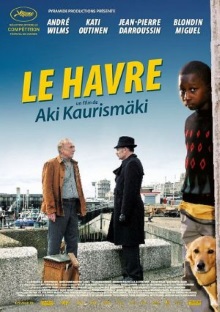

I admit that when I first heard of this movie, my first thought was of the boardgame. Of course, this has nothing to do with that though both refer to the French port city bearing the name. It’s worth noting that while this is a French language film, it was directed by Finnish Aki Kaurismäki, which I think accounts for some of its strangeness.

Marcel Marx is an old man who ekes out a meager living shining shoes in Le Havre. One day the authorities discover that a cargo container at the port is full of African immigrants trying to make their way to Britain. A young boy, Idrissa, manages to escape and out of kindness Marx takes him in despite having problems of his own as his wife is seriously ill. Fortunately for him, this is the kind of film in which the whole neighborhood comes together to keep the boy out of the hands of the police and eventually help smuggle him to London.

What’s strange is that while the story and its context place this film in modern day France, it often looks and feels as if it were set in a much earlier time, an impression reinforced by its cinematography and color choices. Inspector Monet, with his hat, coat and car looks like he walked out of a film noir from the 1970s. Other than Idrissa, every character is old and looks long past their prime. The cameo by Little Bob, an aging rocker, is a highly visible symbol of this at work. Even Marx admits that he was once a Bohemian and an artist, but that is all far in the past.

The other thing is that every character in this film is a paragon of goodness. The film goes out of its way to both show ethnic diversity, Marx’s fellow shoe-shiner friend Chang for example who is of Vietnamese origin, and also how the French are uniformly kindly and welcoming to it. More even than viewing French society through rose-tinted glasses, it’s a vision of France as a timeless egalitarian utopia where all shopkeepers know their customers by name, all bakers are ready to give an extra baguette to those in need and all barkeepers are always happy to lend a friendly ear. As a Finn, Kaurismäki might be able to get away with this, but it would be really odd for a French director to make something like this.

Still, there’s an undeniable charm to it all and it is pleasantly entertaining to watch if you can look past the sentimentality. It successfully paints a portrait of small-town France that instantly makes you want to visit it and no doubt this is how progressive leftists in France would love poor immigrants to be treated in their country. Kaurismäki himself makes it clear where his sympathies lie by admitting that his protagonist is named after Karl Marx. Unfortunately this portrayal is as much a fairy tale as its feel-good ending and as such it’s hard to take Le Havre seriously as a film.

One thought on “Le Havre (2011)”