Double Indemnity is probably a film that needs no introduction. It is considered the paradigmatic film of the noir genre and set the stage for all others noir films to come. After watching it however, I realized that it’s highly unusual even for a noir film. The protagonist in this case is neither a police officer nor a private investigator. Instead, he is, as the audience learns from the opening narration, both the mastermind and the perpetrator of the crime that is at the center of this film.

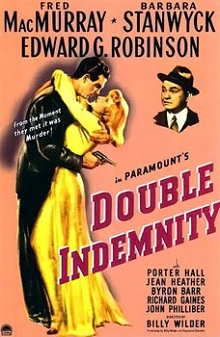

Fred MacMurray plays Walter Neff, a successful insurance salesman who meets the femme fatale of this film, Barbara Stanwyck’s Phyllis Dietrichson while trying to sell her husband some auto insurance. She seduces him and despite his early reticence manages to convince him to surreptitiously buy accident insurance for her husband without his knowledge and then murder him for the money. Neff knows that he needs to beat the keen investigative mind of his own colleague, the company’s claims adjustor Barton Keyes, and so uses all of his knowledge in the insurance industry to engineer the perfect murder.

Since the audience knows who the murderers are and exactly what they do, the suspense of the story lies in seeing if they manage to get away with it. Director Billy Wilder plays this to full effect with multiple scenes that exist only to ratchet up the tension such as when the couple have trouble starting their getaway car or when Keyes pops up at Neff’s home moments before Dietrichson is supposed to arrive. Also great is that none of the characters are left holding the idiot ball. The insurance company’s boss tells Dietrichson that they won’t be paying the claim and advances a plausible theory that the death was a suicide. Keyes turns this around and equally plausibly shows how this couldn’t have been a suicide. It’s smart reasoning and therefore smart writing throughout the film.

Wilder has a reputation as a director that places story ahead of other elements like cinematography and pure acting. The slick plotting of Double Indemnity is great example of this principle in action. There’s an assured flow in everything and a clear purpose to every scene. Stanwyck oozes both sensuality and wickedness while Edward Robinson as Keyes makes for a wonderful foil that Neff needs to keep one step ahead of. The dialogue, co-written with Raymond Chandler, is snappy and memorable, though I for one think that they invoke the “end of the line” phrase one too many times.

The two films that are most frequently cited as the best film noir of all time are this one and The Big Sleep. Now that I’ve watched both, it’s interesting to compare them. This one is clever, with a tight plot that makes perfect sense and characters who impress the audience through their intelligence. However there’s no real romance in it as even Dietrichson’s final confession to Neff feels laughable. By contrast, The Big Sleep has a confusing plot that is full of holes but wins points due to its sense of atmosphere and the smoldering energy of its pairing. Both are well worth watching but it’s no surprise that I prefer Double Indemnity as the more cerebral film of the two.