These are gods who have been forgotten, and now might as well be dead. They can be found only in dry histories. They are gone, all gone, but their names and their images remain with us.

…

These are the gods who have passed out of memory. Even their names are lost. The people who worshiped them are as forgotten as their gods. Their totems are long since broken and cast down. Their last priests died without passing on their secrets.

Gods die. And when they truly die they are unmourned and unremembered. Ideas are more difficult to kill than people, but they can be killed, in the end.

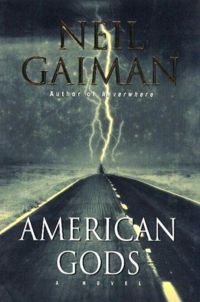

– Neil Gaiman in American Gods.

Quite a few comic book writers have over the years tried their hand at writing novels, but none have achieved as much mainstream success and recognition as Neil Gaiman, winning the Hugo, Nebula and Bram Stoker Awards for Best Novel for American Gods. This is partly explained by the fact that Gaiman actually co-wrote a novel, Good Omens, together with Terry Pratchett, before ever venturing into comics, which he did in a big way, by taking up the mantle for Miracleman following Alan Moore’s departure from the series. Nevertheless, Gaiman is best known for writing the highly acclaimed Sandman series from 1989 to 1996.

American Gods features some of the same themes as The Sandman and deals with the subject of gods, in this case, once great gods whose powers have waned as their worshipers have died off and their religions fallen into obscurity. Set in contemporary times, the novel follows the adventures of Shadow, a recently released convict from prison, as he travels across the United States while working for a mysterious employer, meets with a large number of decidedly odd individuals and learns quite a few secrets along the way, including secrets about himself and the nature of America.

Early on you get plenty of hints that Shadow isn’t just an average convict, beginning with an absent last name that somehow always manages to avoid being mentioned. He does his time quietly and obediently in prison, spending his time reading Herodotus’ Histories and learning to perform magic tricks with coins. He looks forward to a long awaited reunion with a loving wife, a regular job and promises to keep his nose clean and stay out of prison but as these things always go, nothing turns out as he expects and ends up being employed as a bodyguard for a conman named Wednesday.

As Shadow learns on his travels with Wednesday, the gods are real beings who walk the Earth. Brought to life through the rituals and sacrifices of worshipers all around the world and carried to America in the heads of the immigrants who have traveled to the continent for thousands of years, these once great beings have fallen on hard times in modern times. This is because the gods thrive on belief and prayer. With it they gain power and control over their respective dominions; without it they are forced to eke out an immortal but miserable existence, working jobs such as prostitutes, cab drivers and even morticians. Now even this pitiful existence is being threatened by the new gods who have arisen from new beliefs: gods of technology, Internet, highways and mass media. Not content with being the masters of the current paradigm, they have started to actively hunt down and kill the Old Gods, and so, Wednesday, one of the greatest and most well-known of the Old Gods, has taken it upon himself to rally the Old Gods in one last glorious battle with Shadow as his sidekick.

One of the coolest things about American Gods is the plethora of deities who appear in it, even if most are just cameos. If you fancy yourself a student of mythology, try figuring out which pantheons gods like Anansi, Czernobog and Wisakedjak are from. Deities more familiar to most include Anubis, Eostre and Kali. For people who have enjoyed reading folk tales and mythological stories from all around the world, you should get a real kick out of reading about gods from wildly different pantheons interacting with each other in contemporary America. The colorfulness of the characters is matched by the locales such as the House on the Rock and Rock City, gaudy real world tourist attractions that according to the rules of the universe that Gaiman has imagined, have become places of power due to the number of visitors making “pilgrimages” there.

The unbelievably fantastic nature of the events contrasts sharply with the emotionless Shadow, who seems to almost sleepwalk through impossibilities that would drive most people insane. This is explained in the novel as his traumatic response to the tragedies that befall him at the beginning of the novel, but it’s also the author’s literary device to serve as an anchor to reality in the face of all the surreal craziness that goes on. A dead wife who simply won’t stay dead. Dreams that indistinguishably meld into reality. Characters who talk to him and follow him with their eyes whenever he’s alone with a television. Creepy men in black secret agents who belong to no official government agency but manage to get the cooperation of law enforcement officials anyway simply because everyone just “knows” that they exist and are real. You can never tell what Gaiman is going to throw at you with every turn of the page.

It’s arguable that most of the novel is simply a series of entertaining vignettes tied together through Shadow’s wanderings and there are descriptions of gods and their doings that are only loosely connected to the main plot, but in my opinion, there’s still enough meat in the story for the novel to feel like a full and satisfying experience. If you’re expecting a traditional heroic fantasy, you’ll probably end up being disappointed, but if you like reading the kind of legends and tall tales that used to be told around a campfire, plan on spending a few nights curled up in bed finishing this amazing book.