Guru came to my attention when it was mentioned in The Economist and it was featured in a Marginal Revolution post by Alex Tabarrok, who called it the most important free market movie ever. The thing about this film that must be understood is that although it uses invented names throughout, including fictional names for the companies involved, it is really a very loose biography of Dhirubhai Ambani, one of India’s most famous tycoons, who founded the Reliance group of companies. This helps explain why this film is so fascinating to economists.

Gurukant Desai grows up in a rural area in India to a father who is the local headmaster. Having failed his own exams, he goes to Turkey to work and is eventually promoted to a sales manager. To the consternation of all, he declines to pursue that career and instead returns home to start his own business. Since he has insufficient capital, he marries Sujata, the sister of his best friend and business partner, for her dowry. As a beginning textile trader, he finds that his main difficulty is securing the approval of the regulatory entities. When patience and cajoling doesn’t work, he befriends a newspaper editor, Manik Dasgupta, who is inspired by his drive to modernize India and helps him embarrass the local monopolist. His company, named Shakti Corporation, grows incredibly quickly and sells shares to the general public to raise additional capital. But as his company grows and his own influence increases, he is accused of corrupting government bureaucrats and taking short cuts to get things done as soon as possible. The same editor Dasgupta, together with his star reporter Shyam Saxena, become his opponents as they work to expose his wrongdoings.

It’s a great setup and has all the makings of a fantastic story. Unfortunately director Mani Ratnam wastes the opportunity by making a crowd-pleasing film that focuses on all of the wrong things. A good example of this appears early in the film: Mallika Sherawat guest stars as an unnamed belly dancer for a full song and dance sequence. As pleasant to look at as Sherawat is, the scene adds nothing of substance to the film but contributes significantly to its running time. For similar reasons, the most important relationship in the film is that between Gurukant and his wife Sujata, and much screen time is consequently devoted to song and dance sequences featuring the two. That’s all well and good for mainstream audiences but it’s not really what we’re looking for in a biography of one of India’s greatest entrepreneurs.

Even when the film focuses on Gurukant’s business affairs, it has him solving problems in flamboyant and unrealistic ways. When the textile traders in Bombay is shut down by a local official who simply locks the doors to their trading hall, Gurukant decides to transport all of his goods to the official’s residence and annoy him in that way until he relents. Montages and quick cuts are used to show his company’s growing success, without any scenes showing the nitty-gritty details. So one moment he talks about selling shares to the public to raise capital and the next he already has thousands of shareholders. We never learn how he complies with the rules that regulate public offerings, how he educates themselves on them or how he markets his shares. The film attributes his success to his sheer determination, the power of positive thinking and some measure of luck but it does nothing to convince us that he is especially clever or resourceful.

Where this film does strike an original note is also what attracted Tabarrok. This is its ambiguous treatment of Gurukant’s morality. There’s no doubt that he genuinely loves his wife but he also doesn’t deny that he originally married for his money. After being continually beaten down by crooked bureaucrats and entrenched interests when he was starting out, he turns around and uses those same methods when he is successful, bribing politicians and breaking rules to enable his businesses to expand faster. At one point, it gets so bad that I wondered if the film was going to do a full-on face-heel-turn with the reporter Shyam Saxena becoming the hero the audience should be rooting for. Tabarrok reasons that this is a case of virtue trumping the law. Gurukant acts according to his personal moral principles at all times and doesn’t care to obey the law when he feels that they were enacted to protect the interests of the moneyed elite and slow down the progress of India. He points out in particular that Gurukant never uses his influence to impede competitors and never allows these business disputes to harm his personal relationships. It’s an interesting argument and this portrayal certainly makes this a better film, but it’s not altogether airtight. For example, he appears to indulge in fraud to inflate his profits and deceive his shareholders, actions that are hard to square with any personal virtue.

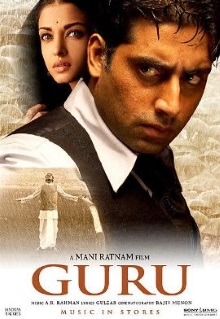

Abhishek Bachchan’s performance as Gurukant is worth making special note of as he has to play him both as an enterprising youth and as a paunchy old man partially paralyzed by a stroke. Aishwarya Rai, the so-called most beautiful woman in the world, is once again pleasant eye-candy but doesn’t have much to the film. On balance, this is a film that could have been great but chose to go for mainstream appeal rather than seriousness. The life of Dhirubhai Ambani is colorful enough and historically important enough to deserve a good biographical film, but this isn’t it.