My wife’s first reaction as we walked out the cinema after watching Prince Caspian was “Aslan is such an asshole.” Indeed he is, and in the same way, so is the personage after whom Aslan was clearly modelled, Jesus Christ and the Christian God.

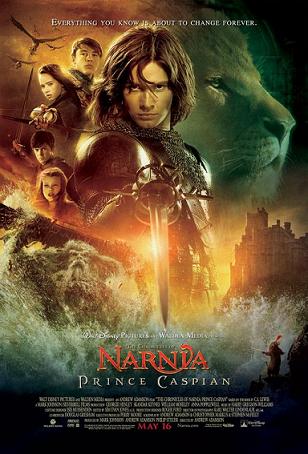

This second installment of the Narnia series based on the novels by C.S. Lewis has been marketed as a harmless, big budget, family-friendly, action adventure fantasy flick. So harmless and family-friendly that no blood whatsoever is shown on screen even as Gentle Queen Susan perforates countless enemies with her arrows and Magnificent King Peter hacks and bashes his way through the Conquistador-like opposition. But I can’t help but wonder how many of my fellow Malaysians who sat with me in the same cinema were aware of the Christian agenda behind the novels and the films it has inspired. In a country so paranoid about religious sensibilities that The Passion of the Christ was banned in cinemas and the word Allah was, initially anyway, forbidden to be used by a local Christian newspaper to describe the Christian God, it’s a wonder that Prince Caspian is being shown on Malaysian cinemas with an “Umum” rating.

The fact that the original books contains strong parallels to Christian imagery and mythology is well established and doesn’t need to be dwelled upon. What might be less well known is that the film versions were explicitly meant to uphold Christian values and teachings as well, as this interview published in The Economist with Philip Anschutz, who owns the production company Walden Media, makes clear. But while The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe showed the more benign side of Aslan, who nobly sacrificed himself to save Edmund and being subsequently resurrected just in time to save the day, Prince Caspian arguably shows a darker, more Old Testament, side of Aslan.

In Prince Caspian, the Pevensie children are summoned back to Narnia some 1,300 years after the end of their reigns as the kings and queens of Narnia. During their absence, a race of men known as the Telmarines have invaded Narnia and rendered the native peoples and Talking Beasts nearly extinct. As the numbers of the Narnians have dwindled, so has belief in Aslan and one dwarf, Trumpkin, even openly scoffs at the thought of putting his faith in him. Naturally, it is up to the Pevensies not only to overthrow the despotic King Miraz and restore the throne to its rightful owner, Prince Caspian, but also to rebuild the old and rightful religion of Aslan.

Aslan does eventually makes an appearance and, predictably, it is his intervention that turns the tide in favor of the good guys, but he sure takes his time doing it while his people are being slaughtered. It is Lucy, the youngest of the Pevensie children, who first see Aslan after they return to Narnia. The others see nothing and attribute it to Lucy’s overactive imagination who at first fails to go in search of Aslan because she does not have the support of the others. When she does finally find Aslan, she asks, “Why didn’t you come to help us sooner?”

To which Aslan replies, “Why didn’t you come to me sooner?”

These lines are heavily resonant with Christian meaning. Aslan makes it clear that as God, it is not he who needs the Narnians, but the Narnians who need him, and so it is up to the Narnians to call upon him and in effect, pray to him. If they fail to do so, then he will not come and whatever befalls the Narnians is not his responsibility. When he finally does make his move, his omnipotence is not in doubt. The Telmarine army is effortlessly repelled and it is clear that Aslan could have done it and saved his people at any time during the previous 1,300 years while they were being massacred and oppressed, but he didn’t do it because presumably they didn’t believe in him enough and didn’t call on him.

Another revealing pair of lines is when Susan asks Lucy, “Why is it that only you saw Aslan? Why didn’t I see him?”

And Lucy replies, “Maybe because you weren’t looking for him.”

Again, the lesson is clearly a Christian one. God is always there. If you cannot find him, do not blame him for not being there, but blame yourself for not searching for him with all your heart.

To a Christian, all this might seem like a great way to give familiar themes and lessons a fresh coat of paint if they can get over the fact that Jesus is now a lion, but to someone like me, it’s an ugly reminder of how fickle and petty the Christian God can seem to be if you read the Bible literally. When Aslan finally appears, the doubting dwarf, Trumpkin, is brought to him on bent knees and Aslan roars at him, no doubt to let him know just how viscerally real Aslan is. Even the final scene suggests a fickleness unbecoming of an infinitely powerful deity. Aslan offers the surviving Telmarines the chance to return to their world, and when a handful of them accept, Aslan mentions that because they were the first to volunteer, their lives in the new world will be a good one. Presumably those Telmarines who questioned Aslan’s good faith were cursed to lead miserable lives which sounds just like something the god of the Old Testament would do.

Besides the Christian angle, observant viewers might also note that the film shares some striking similarities with the film adaptations of the Lord of the Rings. Giant trees come alive to rescue the Narnian army at the very last minute. Aslan and Lucy block the path of the Telmarine army at a narrow bridge. Aslan calls up a huge tidal wave to wash away the Telmarines. Haven’t we seen all this before? In fact, C.S. Lewis was a close friend of J.R.R. Tolkien and both of them were members of the same literary group at Oxford University, called the “Inklings”, so it’s not so surprising that they borrowed some elements from each other. It’s worth keeping in mind though that while The Lord of the Rings was published later than the Chronicles of Narnia, Tolkien’s trilogy was actually written earlier.

In any case, I admit that I had an enjoyable enough time watching this film. It’s after all a decent action adventure flick in the fantasy genre even if the Christian messages in it make me cringe and I do hope that the film producers manage to work their way right up to the final book in the series, The Last Battle. Many reviewers have mentioned how dark Prince Caspian seemed compared to its predecessor. Wait till they see what Aslan does then.

I did not know that this Narnia series is loaded with Christianity stuff until you mentioned it in this article. O_O

Then again, I did not watch both Narnia movies so I do not really know.

Anyway, my principle belief system is strongly based on Buddhism, and some limited knowledge in the rest.

What is your principle belief system aye?

This is kind of hard to explain succinctly, but I’m an atheist, believe strongly in reason and value self-interest.

Dun see whats the big deal with a big budget Disney movie having Christian, Muslim or Hindu values in it. The Golden Compass has atheism in it, but we dun call for it to be banned. Educate, not isolate 🙂

But I didn’t call for it to be banned. I simply intended to point out that it is a film with overt Christian values, a point lost on many Malaysians and to use it as an example of the fickleness of the Christian god.