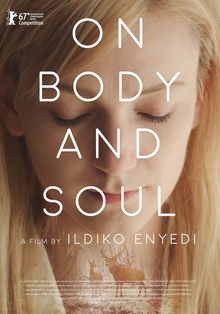

I’m pretty sure we’ve never watched a Hungarian film before but this is only one of two films from that country currently on my list. It was directed by Ildikó Enyedi, a female Hungarian director who appears to have quite a respectable filmography. It’s all new to us of course but I do note with some interest that the film’s credits appear in both Hungarian and English and its main song is by Laura Marling, a British folk singer.

Endre is the financial director of a slaughterhouse that processes cattle on an industrial scale. He lives by himself with some difficulty due to a crippled arm and has given up on romantic entanglements due to his advanced age. One day the factory hires a new quality control inspector, Mária, who quickly becomes the topic of gossip among the staff due to her complete inability to socialize and her obsessive-compulsive behavior. Endre attempts to befriend her but is rebuffed by her rudeness. When the company’s store of a drug meant to induce mating in cattle is stolen, the police are called in to investigate. They suggest using a psychologist to interview all staff with access to the drug, which includes Endre himself. Part of this process involves asking the participants about their dreams, revealing that Endre and Mária somehow share the same recurring dream of being deer in a forest.

This film has the sort of thoughtful, meditative quality that critics love. The cinematography is excellent and some of the images, with their stark colors, are genuinely striking. The close-up shots of the eyes of the cows and the deer for example make it seem as if they are intelligent beings capable of a wide spectrum of emotions. The net effect is a powerful and moving portrayal of two seemingly linked souls through imagery alone without needing to put it into crude words. I like how both characters bring their own baggage into the relationship, Endre with his inferiority complex and fear of being hurt and Mária with her inability to navigate conversations and reliance on scripting every social interaction in advance. It’s fascinating to watch Mária learn to accept her emotions though I am frustrated that Endre doesn’t seem to grasp the fact that she is psychologically impaired and isn’t being deliberately rude.

On the other hand, certain scenes and imagery choices don’t seem to coalesce in a meaningful way in support of the film’s themes. Early on the camera lingers on the eyes and faces of the doomed cattle, as if to show their awareness and apprehension of their fate. Then the camera moves on the deer, suggesting that there is some sort of link there. Yet nothing comes out of this thread and the two main characters never express any regret for their work or sympathy for the animals. Similarly the side-plot about the theft at the abattoir feels in the end like only an awkward way for the two to come to the realization that they share the same dreams. When their relationship gets going, everything else gets left by the wayside, which feels odd and unsatisfying.

On the whole, while its lack of cohesion makes it a less than perfect work. I would consider this an excellent film. Its highly sensitive portrayal of vulnerability is extraordinary and using animals to visualize two people sharing a deep connection is inspired. It makes for a great first impression for Hungarian cinema.