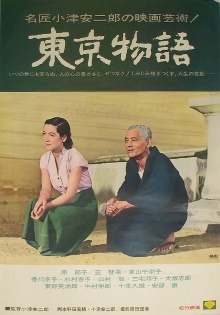

This is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made and, yes, here I am watching it for the first time. In fact, I believe this is the first time I’ve watching anything by director Yasujirō Ozu and as my wife remarks this means we’ll be in for a string of his other works down the road. This is a minimalist film with a highly traditional story so at first glance it might hard to see what the fuss is all about. But there is a kind of sublime beauty in its simplicity and its understated style helps it convey deep emotion without feeling melodramatic.

An elderly couple who live in the town of Onomichi decide to visit their children who apart from the youngest Kyōko have moved to live in the cities. They start with their son Kōichi who is a doctor in Tokyo and stay in his house. However Kōichi is always busy with his patients. So is Shige, the eldest daughter who runs a hair salon. Though they discuss plans for various activities together these never pan out as they are too busy. It is up to their daughter in law Noriko, wife of their son who died in the war, who brings them around to tour the city. After that, Kōichi and Shige pay to have the parents go stay at a hot spring spa to get them out of their way. They end up disliking the place as it is meant for a younger clientele and is too noisy and busy for them. When they return to Tokyo earlier than expected, their children have difficulty hosting them as they have already made other plans.

The film moves at such a sedate pace that it takes a little while to get what the director is going for, a feeling that is reinforced by the passive camera. This is a film with little drama and absolutely no histrionics. The old couple Shūkichi and Tomi maintains an air of good-natured affability throughout. They never express any disappointment or discontent towards their children, and even when the grandchildren behave badly, they just wave it off with a tolerant smile. The same goes for the children who never actively malicious or cruel. They are simply neglectful and have other priorities in their lives. As the kindly Noriko explains to Kyōko who is infuriated by the behavior of her older siblings, children inevitably drift away from their parents especially once they have families of their own and have to think of them. This film’s resolute refusal to assign blame gives it tremendous moral authority as it presents this simply as a truth of the world. As I’ve read elsewhere, this is why Tokyo Story feels quintessentially Japanese even though it was adapted from a previous American film.

All the same, I did find the film a little too on the nose at times, with one of the sons repeating the phrase “no one serve his parents beyond the grave” twice or how Noriko is shown as the one who lives under the poorest conditions. Similarly the use of shots of smokestacks and the like to represent the corrupting effects of the city is kind of trite. This tells me that as subtle and nuanced as this film is, it is still a product of its time. It may be highly restrained in its style but it does still want to moralize. I am also biased in that I am not personally sympathetic to its affirmation of traditional Japanese values. All told, it is understandable why this is considered as great as it is and I certainly enjoyed it very much. But I wouldn’t ever consider it one of my favorites.