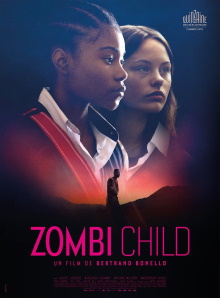

As the title states, here is yet another zombie film even as we are working through the South Korean series Kingdom. Happily this one hearkens back to the original meaning of the word before it was commercialized by American films. Though framed as a fictional story set both in Haiti in the past and present day France, I feel that it is works better like a documentary that is meant to introduce to us voodoo and that entire aspect of Haitian culture.

The narrative that starts in Haiti in the 1960s involves a man who seemingly dies and is interred. But his coffin is dug up and he is turned into a zombie to work in a plantation. Meanwhile in the present, Mélissa is a new student at an elite school in Paris open only to those whose recent ancestors have been awarded the French Légion d’honneur. In her case, her mother was granted that award for her human rights work against the dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier in Haiti and she moved to France after both of her parents were killed in the earthquake of 2010. A French girl Fanny recruits her into a literary sorority where she recounts some of the poetry and stories from Haiti. Back in the past, the man is awakened from his zombie state and escapes, but spends his days wandering instead of reuniting with his family. Mélissa recounts this as the story of her grandfather and that her aunt with whom she lives in France is mambo practitioner of voodoo.

The scenes set in the present are straightforward to understand though the viewer is left a little off-kilter as we see Mélissa through the perspective of her friend Fanny. Those set in Haiti are more obtuse as there is hardly any dialogue and next to no explanation at all. Eventually things do become clearer and I understood that the intent is to educate viewers about Haitian culture. Instead of being impersonal and distant like a conventional documentary however, this approach of embedding it in a story emphasizes the emotional power and intuitive rawness of voodoo. As Mélissa explains, the most powerful and famous figure in the religion, Baron Samedi, is both God and Devil and invoking him does not come without consequences. When Fanny begs Mélissa’s aunt to perform a ritual for her, the experience is therefore appropriately horrifying and impressive. The film never even attempts to address critical questions such as the logistics and biological details of how zombies work or how literally real this all is. But by framing it within a story, it argues indirectly that this isn’t a subject that ought to be understood within a rationalist mindset anyway.

Anyway, while this film works fairly well as an introduction to voodoo, the story parts are rather bare and unsatisfying. All of the characters in the scenes set in Haiti are never quite real, distant as they are from the audience. The scenes in France are interesting as I never knew that such a school exists and their curriculum is certainly impressive. But the triviality of Fanny’s personal problems is grating, as they’re there only to push her to seek out Mélissa’s aunt. It’s frustrating that the film dwells on Fanny instead of trying to reconcile Mélissa’s place in modern France with her resolute confidence that voodoo is genuine. I suppose it is admirable that the film insists that Mélissa is just an ordinary girl in France is all respects and that her belief in voodoo is just something extra added on, but I’d bet everyone would be much more interested in learning more about her than about Fanny.

That’s why I’d say that this works okay as a primer on voodoo and to remind the world of the original meaning of the word zombie but it’s rather weak as a film. Director Bertrand Bonello has good intentions but I think as he is himself French and not Haitian, he does not have the direct and personal connection to the subject to bring it fully to life.