It’s been a while since I sat down and read a proper non-fiction book. It’s not that I’m uninterested, it’s just that I read so much non-fiction online already that I don’t feel the need to do so to generally stay on top of current events and discoveries. This book however has been talked about so much among the economists whose blogs I keep up on that I felt compelled to buy it and really history is one of the subjects that it is better to read a proper book about than gain knowledge about through osmosis. Do note that I’m dispensing with the subtitle that is always so annoyingly long in modern non-fiction books and the author Steven Johnson is not himself a historian but a popular science author so this book is aimed at the mass market.

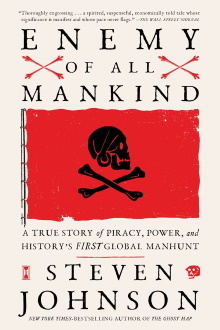

You should still be able to read the subtitle in the picture above clearly enough to tell that this is a book about one pirate in particular, so notorious in his time in the 17th-century that the book argues that he was first terrorist to be the target of a global manhunt. His name is Henry Every and his great crime was to raid the Ganj-i-Sawai, a fabulously rich treasure ship of the Grand Mughal of India, then returning from the annual pilgrimage to India. The scale of the crime is compounded by the days-long ordeal of murder, rape and torture that Every and his crew inflicted on the crew and passengers of the Indian ship, including possibly the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter or granddaughter. The horror of the attack prompted the emperor to accuse Britain of being a nation of pirates and threatened an end of all East India Company activities in India and hence all Indian trade with Britain. The potential financial damage was great enough to move the great and the good of Great Britain to definitively condemn all forms of piracy, launch a manhunt for Every and his crew and to make examples of them.

This is a surprisingly short book, especially compared to the fantasy and science-fiction epics I’m used to, and it’s an easy book to read as well. At first I was even concerned that the book goes too far in dramatizing events as it opens with an exciting account of the battle between Every’s ship, which he had named the Fancy, and the Ganj-i-Sawai. As the Mughal ship is far larger and more heavily armed, Every achieves victory only due to such fantastical good luck that you would call it out for being fake if it were a movie. Yet this really was what happened and as far as I can tell everything in this book is meticulously researched and attributed to reliable sources. In places where Johnson makes some educated guesses about what might have happened or have been said, he makes it clear that this is pure supposition. Though Every is virtually unknown except to historians today, he was a celebrity in his time and there was plenty of tall tales and published stories about him that amounts to fan fiction. Johnson recounts many of these stories to give the reader an idea of what the general public of the time were told but again, makes their dubious nature clear. All this is to say that while this is certainly an entertaining and engaging non-academic book, it’s still a serious history book and takes great care to get things right.

Perhaps the best test of how valuable a non-fiction book is lies in how much you can truly learn from it, how many insights and facts you can glean from it that are non-trivial. In that sense, this book is a virtual goldmine as hardly a page goes by without me learning something new that is worth rearranging my mental model of the world for. The exploits of Every and his gang of pirates make for a great story but what really drew me in is the endless succession of things to be learned ranging from the relatively trivial such as the disgusting food that all seafarers must endure after months at sea and the first thing pirates usually do after seizing a ship to turn into a pirate vessel is to demolish the structures above the deck both to streamline the ship so it can go faster and to eliminate the captain’s cabin to establish a more egalitarian command structure. But even these observations usually lead to deeper insights such as the fact that pirate society should be more egalitarian and democratic than anything else the English would have known in that time. Then there are the revelations that are mind-blowing to me but are treated as mere asides in the book, including the theory that the Muslim Mughals managed to gain total control of trade in India due to Hindu teachings that discouraged any form of long distance travel. Readers will probably also be surprised to learn that the average European of the period would perceive the Mughal civilization as being richer and more sophisticated than their own.

Of course, I was introduced to this book by economists and so it’s no wonder how much economics there is in it. We learn about just why the Mughal Empire was so rich at that time, thus attracting the attention of pirates. One of the first things Every’s crew does with their loot is to buy slaves with it because it is considered a very liquid form of wealth and being seen as slave traders actually helps them pass as being legitimate. There’s also a bit about the history of the East India Company and its troubles with the British government at the time of the attack but the managers succeeded in turning the crisis into an opportunity. Johnson argues that the agreement between the company and the Mughal Empire to use the company’s naval assets to hunt pirates in Indian waters after the attack helped entrench the company as its own military and led to the company gaining control of the entire subcontinent. There is so much to learn in this book and every bit of it is fascinating. I frequently found myself wishing that the book was longer as I wanted more elaboration on some topic or another.

One particular point of elaboration that I’d hoped to see was the reactions of the other world powers of the era. The book covers pretty much only the reactions of the British and the Mughal Empire to the raid. Every recruited crewmembers from other European nations by preying on their vessels but that only made me more curious about what their governments thoughts of the whole thing. In particular as the incident eventually led to the East India Company being the de facto naval power in Indian waters, surely the other Europeans power ought to have tried something to contest that supremacy. But that just means that I have lots more to learn about history and much more reading to do. Anyway this is an amazing history book written for laymen and deserves every bit of the success it has earned.