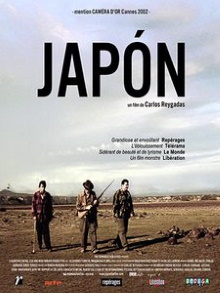

After watching and liking Our Time so much, I said I’d have to look into director Carlos Reygadas’ older films and so we start with this, his very first feature film. I have no idea why it’s called Japón even after finishing it and in general I found this harder to parse than Our Time. On reflection, in addition to the obvious subject of suicide, I believe that the main point is the Christian motif of turning the other cheek to the point of self-sacrifice. I can’t say that I liked this as much but I can appreciate its visceral power which even the crudeness of its production values helps enhance.

A man who refuses to give his name arrives in the countryside where the land descends into a large valley. He encounters a group of hunters and asks for directions to get to the bottom of the valley. They agree to take him halfway to a small town on the slopes with their truck and he has to walk the rest of the way. When asked why he wants to go there, he eventually replies that it is to die. He spends the night with them and then sets off the next day though he limps on a bad leg and must use a walking stick. At the village at the bottom of the valley, the villagers wonder why he has come but seem happy to attract visitors. When he asks if he can get a place to stay in the village, they refer him to an elderly widow who lives alone. The man calls her Ascen and stays in her barn. Though she says that she is too old to serve him, she is nonetheless a very hospital host. Throughout his days there, the man takes long walks in the village and on the mountainside. He has a gun with him but doesn’t seem quite able to pull the trigger. He is also upset when Ascen’s nephew demands that the barn be demolished so that he can get its stones for himself and she passively does not resist.

As another one of those films that has almost no plot it’s all about capturing the feelings of the main character on a moment by moment basis without recourse to any internal monologue. The countryside that he visits is certainly not idyllic. The daily routines of life there call for heavy physical labor and wears down on the people. They drink copious amounts of alcohol and sing crude songs as entertainment. Nature is brutal and cruel. Reygadas uses unsimulated shots of genuine animal suffering to make his point and this is a major point of contention to critics. In one early scene, a young boy is isn’t strong enough to snap the neck of a bird and leaves it injured. The main character then takes over and tears its head clean off. Against this backdrop, Ascen’s devotion to Christ and infinite capacity for empathizing with others stands out ever more starkly.

We never quite get the full story of the main character’s life but we do get some clues to speculate on our own. We know that he is a painter but seems to have soured on his own work. We know from his dreams that his reasons for wanting to kill himself probably have something to do with a woman. The question becomes how exactly does his time in the countryside dissuade him from suicide. My interpretation is that the isolation and the raw stimuli of untamed nature reawakens desires and feelings in him. His sexual desire is aroused even by the very old Ascen while her passive acceptance of whatever might happen to her seems to make him feel indignant on her behalf. At the same time there is a Christian grace in Ascen’s putting everyone before herself. I dislike this sort of message but I concede that there is a lyrical power in it.

On the whole this film resonates with me far less than Our Time. The director defends his use of animal cruelty in that this reflects the reality of life in the countryside but even so the film treating it as being perfectly normal and hence acceptable is problematic to me. This first film serves as an excellent showcase for the director’s mastery of using visuals to provoke a visceral and powerful emotional reaction. But the themes and the cause he deploys those skills in service of in this instance is not that well conceived.