I must confess that I have an irrational attraction to all screenplays written by Charlie Kaufman. Being John Malkovich was weird and silly but a complete delight all the same. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is nothing less than one of my favorite films ever. So it was inevitable that I would eventually get around to watching Adaptation, even though it isn’t generally considered to be one of his better efforts. Please note that this post will be chockful of spoilers because it simply isn’t possible to discuss the film in sufficient detail otherwise.

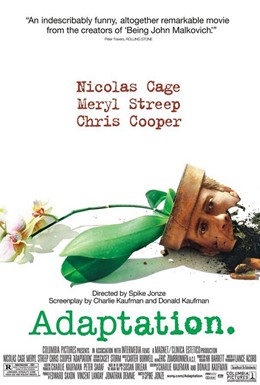

Adaptation is very generally a film whose story is about the story of the film itself as it is being created. As such it is intensely self-referential. The main character of the film is a fictionalized version of Charlie Kaufman himself, played by Nicolas Cage, trying to write the screenplay of the film that would become Adaptation. In the film, Kaufman, following the success of Being John Malkovich, has been hired to write the screenplay for a film adaptation of Susan Orlean’s novel The Orchid Thief.

Kaufman however fails to write the screenplay as he is reluctant to sensationalize the events depicted in the novel by giving it the Hollywood treatment. He keeps trying to write a script that is faithful to the novel but finds it difficult to do so as the novel is so bereft of conflict or drama. At the same time, his twin brother Donald Kaufman, also played by Nicolas Cage, decides to be a screenwriter as well and incorporates all of the worst Hollywood clichés in a script that nevertheless is tremendously successful.

Desperate, he spends his time instead writing about himself trying to write the screenplay and failing. He even finds himself attending a seminar on writing stories given by Robert McKee upon the advice of Donald, despite his initial scathing dismissal of the writing class as stereotypical nonsense. After roping in his brother to help him complete his script, the film, and therefore the script itself, transforms into the perfect example of the Hollywood stereotype that he was trying so hard to avoid.

The surreality of the film’s premise is enhanced by the way that it mixes fact with fiction. The character of Donald Kaufman is wholly fictional even though he is credited as a co-writer for Adaptation. Susan Orlean and her novel however are both real and in fact Charlie Kaufman really was hired to write a screenplay to adapt it but suffered from writer’s block and turned in this monster of a script instead. Robert McKee is real as well and is one of the most influential and famous scriptwriting teachers today but is sometimes criticized for teaching people how to write scripts without having a script of his own being successfully turned into a film.

This makes the entire film either a terrifically brilliant experiment and artistic statement or a colossal joke. In support of the latter view, I submit that anyone who has ever made a serious attempt at writing fiction must have at some point in their lives done the exact same thing as Kaufman has in the film. I know that I’ve sat down at a keyboard before, forcing myself to adhere to a strict discipline to write something, anything for the sake of the practice, and turned out something like, “So here I am sitting down at the keyboard thinking about what to write…” I guarantee that if you were to look into the reject pile of any writing workshop, you will find multiple iterations of the same idea.

The difference of course is that for the rest of us, the results of our self-indulgent wankery wind up in the trash and we’re too embarrassed to ever bring up the subject again. Kaufman however not only fully embraced his creation, but actually managed to get it financed with a multimillion budget and brought in some of best talents in film-making to get it done. The performances in the film are all superb. Nicolas Cage as a balding, ugly, overweight and unloved script writer is completely different from anything else you’ve seen him in before. Meryl Streep at first appears to conform to her expected character type but then ends up radically subverting it.

This means that I am disgusted and impressed by the film all at the same time. I have to admit that despite the ridiculousness of the premise, Kaufman pulls out all the stops to make the shtick work. The self-referential circularity of the film itself is subjected to lampshade hanging by having Kaufman himself explicitly point out Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. Even the climatic confrontation in the swamp is resolved through precisely the same kind of deus ex machina that McKee warned Kaufman not to use.

Some films can be watched and enjoyed over and over again. Others you watch once and then never bother with again, not because it’s bad but because it relies on a single trick that only works once. Adaptation not only falls squarely into the latter category, but if I ever see another film try to get away with the same thing it will be too soon. Still, it’s such a unique film so devoted to its central gimmick and so skillfully carried out that it’s hard to argue that it doesn’t deserve a viewing. Like it or not, there’s no doubt that this is something that only Kaufman could have pulled off with such panache.