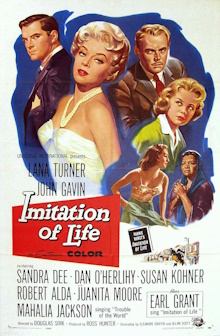

We’ve only watched one other film by Douglas Sirk and it was the very surprising romance All That Heaven Allows. This one, Sirk’s last film, similarly has the superficial trappings of a Hollywood soap opera but is shockingly rich with issues of racial identity and gender roles. It gets seriously dark at times and I wondered if it were only because Sirk is German that he is able to dissect American society in this way. Its main failing is that it’s a little too long and even so its ending is a bit of cop out, meandering to a stop without a satisfactory resolution. Still it’s one of the most fascinating films of the era and is so bold that it should raise eyebrows even now.

On an outing at a very crowded Coney Island beach, widow Lora Meredith momentarily loses track of her daughter Susie. She finds her playing with another girl her age, Sarah Jane. She is somewhat surprised to find that though Sarah Jane passes for white, her mother Annie is definitely black. Though Lora herself is struggling to find work as an actress, she takes in Annie and Sarah Jane when she learns that they are homeless. She also befriends Steve, a photographer. Lora’s career starts slow when she rejects an agent’s insinuations that she may have to offer sexual favors in exchange for roles. But then she impresses a playwright who makes her his lead actress in all of his stage comedies. Lora has to give up her burgeoning romance with Steve for the sake of her career while Annie manages her household and raises the two girls side by side. As they grow up, Sarah Jane increasingly resents being seen as black and wants to be white while Susie, after spending more time with Steve, finds herself falling in love with him romantically.

The film starts out as being seemingly about a woman with agency and such a strong drive for success that she won’t let being a single mother stand in her way. But it grows to be so much than that, encompassing racial roles as Annie becomes her live-in housekeeper, the uncomfortable question of whether Lora is an irresponsible mother by pursuing her career, Sarah Jane wanting a better life for herself as a white woman, and much more. It’s really so dense and complex. For example, Lora rejects her agent’s crass proposal but doesn’t hesitate to become the lover of David Edwards, the playwright who makes her his star. What’s fascinating is that there is rarely any straightforward judgment of what is right and what is wrong. It’s terrible of Sarah Jane to pretend to be white and deny that Annie is her mother but isn’t that also her having agency and wanting a better life for herself in an American society where the racial divide remains a reality? Similarly Lora has never been unkind to Annie or Sarah Jane, yet despite their years of familiarity with each other, she is unaware of Annie’s being part of a black church and her relationships with the wider black community. It makes for a devastatingly sharp portrait of America in the 1950s.

Unfortunately this film still lacks the chutzpah to go all the way. Steve tells Lora that he won’t wait around forever for her, yet promptly dumps his girlfriend once Lora announces that she’s done with her acting. The ending arrives abruptly, seemingly in order to close things out on a positive note. Reading up on the novel this was based on, I see that this film version was changed in many ways. Lora is an actress instead of a businesswoman because acting is more glamorous and allows Lana Turner to wear a plethora of expensive gowns. Steve is a photographer instead of a younger man who works for her. The novel seems so much more authentic and relevant. I’m still impressed by what Sirk dared to make at the time but it feels like the novelist Fannie Hurst was the one really breaking new ground. Interestingly Sirk commented that he deliberately shifted to focus away from Lora over time so audiences go in thinking it’s about an actress but then find that it’s more about Sarah Jane’s struggles over her racial identity. Certainly that conflict is more interesting that the one about Lora’s acting career.

This is now considered one of Sirk’s masterpieces and I’d agree as it’s so well put together and so boldly dissects American society. But it’s also hard to see past the fact that this is prettied up version with the all the truly hard edges filed off and inconvenient details forgotten. Neither Lora nor Susie, for example, ever mention her deceased husband. It’s so strange that a single mother struggling to get by would latch on to an acting career. I’m aware that part of the problem is that this film was so ahead of its time that we are inclined to judge it by modern standards. Certainly we wouldn’t expect such brutal honesty from comparable films in the 1950s. This means that it is a success even if we’d hoped that it would go even farther.