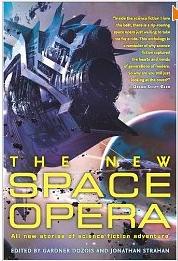

My wife mocks me for taking the better part of a year to get around to finishing this book. In my defense, I offer the following excuses:

- I’ve been busy catching up on my backlog of The Economist issues.

- With 18 stories in all, it’s a pretty hefty collection.

- Many of the stories are good but not great science fiction, and most would barely fit under the space opera label at all.

I don’t want to get into a lengthy discussion of what space opera is, let alone what “new space opera” would be. Suffice to say that old or new, space opera evokes images of starships and space battles, rip roaring action adventure on a grand scale and larger than life heroes. Think Star Wars instead of Star Trek (the pre-retcon version anyway). Most of the stories in The New Space Opera don’t really fit this mould.

Some of the stories that most resemble the grand space opera of old include “Verthandi’s Ring” by Ian McDonald and “Minla’s Flowers” by Alastair Reynolds. This is no surprise as both are well known as two of the best space opera writers currently active. “Verthandi’s Ring” is a good example of solid space opera with a post-human twist, featuring fantastically alien factions fighting a war so vast in scale that they casually toss entire planets at each other. “Minla’s Flowers” is smaller in scale, about the process of bootstrapping a nascent civilization enough so that they can escape an impending alien invasion. With its strong focus on individual characters and how they develop, it’s the more affecting of the two stories.

Adventure stories involving intrepid explorers count as space opera as well, especially if they involve a good dose of armed conflict. Good stories in this vein include Robert Reed’s “Hatch”, based around an odd community that struggles to survive on the surface of a massive but apparently ruined alien starship. Mary Rosenblum’s “Splinters of Glass” is another example, about a protagonist desperately trying to escape a cadre of assassins on the ice of Europa. Then there’s “The Worm Turns” by Gregory Benford. No fighting in this one, but trying to survive harsh environmental conditions is another staple of space opera and this story the environment happens to be the inside of a wormhole.

The single best story in this collection is probably the novella “Muse of Fire” by Dan Simmons. It’s set in a galaxy in which humans been conquered and enslaved by incomprehensibly powerful alien beings. Their only hope of salvation appears to be a troupe of traveling actors and how well they can perform Shakespeare’s works. It has the grand scale of space opera but it’s quirky plot and final twist, about no less than defying the gods themselves, seems like it belongs more in Star Trek than Star Wars.

Other good pieces that I nevertheless don’t really think of as space opera are Ken MacLeod’s “Who’s Afraid of Wolf 359” and Tony Daniel’s “The Valley of the Gardens”. The former is a cautionary tale about the dangers of sending the wrong person to fix a problem that could threaten the galaxy while the latter is a love story about two individuals who must exist in entirely separate realities even though only a line in the sand separates them. Another decent story would be “Remembrance” by Stephen Baxter about how humans cope with a devastating tragedy simply by having the entire species forget it ever happened.

Most of the other stories didn’t really work for me. Robert Silverberg’s “The Emperor and the Maula”, Peter F. Hamilton’s “Blessed by an Angel” and Nancy Kress’ “Art of War” rely on plot contrivances that are entirely too trite. The first story basically reuses the same framing device employed by Scheherazade in the One Thousand and One Nights while the second one is about angelic beings surreptitiously impregnating humans and the governing authority’s secret efforts to fight against them. The third one is about a lonely but ignored researcher’s discovery that the behavior of the terrible alien force threatening humanity can be predicted by studying their art.

James Patrick Kelly’s “Dividing the Sustain” features an interesting cast on board a starship heading out to a new colony. But I found the plot to be nothing to get excited about. The same thing could be said for Kage Baker’s “Maelstrom”, about the creation of a live theatre company on Mars. Personally, my biggest disappointment is Greg Egan’s “Glory”. Egan is easily my favorite science fiction writer and in this story he starts out by posing an interesting question that I’ve always wanted him to answer: what should an enlightened, post-singularity civilization do when it encounters a barbaric, planet-bound one that is still wedded to illiberal ideas about warfare and mass genocide? Unfortunately his story veers off on another tangent entirely and fails to supply a satisfying answer.

On the whole, I have to damn this book with faint praise as an okay but hardly outstanding collection of stories. There’s nothing in here that will really stick in your mind and there are no really new ideas. Worse, few of the stories set the pulse racing as good space opera stories should so you might be disappointed if you bought it based solely on its title. Still, it’s not bad as a form of entertainment and it does provide a decent dose of science fiction for those in need of a fix. Given how poorly the market for science fiction short stories is doing nowadays, consider it a bonus that buying this would help keep the genre alive.