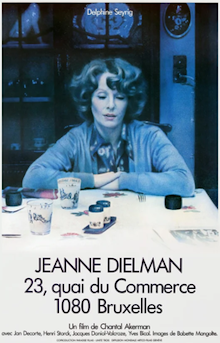

Lists of the greatest films of all time are usually topped by titles like The Godfather, Citizen Kane or something by Alfred Hitchcock. So it was a shock a couple of years ago when this work by Chantal Akerman arrived at the top of a respected poll. This made it an obligatory watch but I took a while to get around to it as it is very long and is said to be very boring. Indeed this can be considered a snooze fest and it requires patience to get through. Yet as critics have noted, there are subtle differences in the daily routine of the titular character across the three days and it does end in a rather dramatic climax. I do think I mostly understand what it’s trying to say and I can appreciate its significance in portraying a female perspective of life but I can’t say it especially resonated with me.

Jeanne Dielman lives in a small apartment at the stated address with her son Sylvain. From a letter written to her by her sister who lives in Canada, we learn that her husband died six years ago. The film follows her more or less fixed routine over the course of three days. We see that she makes a living by being a prostitute, having sex with a man every afternoon in her bedroom before her son comes home from school. Yet that sex too is merely a rote act, inserted into her daily life. In meticulous detail, we watch her wake up, make breakfast, wake her son up, clean up and so on. On the second day however, there is a subtle change in her behavior after the client leaves in the afternoon. She looks frazzled with her hair undone, forgets the potatoes on the stove leaving them overcooked and makes similar small mistakes. That night, Sylvain attempts to have a conversation with her about sex due to comments from one of his friends but she brushes him off. On the third day, she attempts to follow her fixed routine but seemingly feels empty and possibly depressed. In between chores, she sits down and does nothing at all for long stretches, not even reading something or turning on the radio, until the client of the day arrives.

This is a film with fixed camera angles, extremely long takes, no music, no closeups and very little dialogue. It doesn’t take long for you to wonder what’s the point of following a very mundane life in such meticulous detail. But as the critics point out, by starving the audience of stimulation, you become attentive to every minutiae of Jeanne’s life, wondering why for example she keeps going in and out of the few rooms in her apartment and must turn on and then off the light every time. You notice that she places the pajamas for herself and her son under their respective pillows and that she obsessively cleans herself and then the bathtub after every encounter with a client. Its sheer length and the fact that nothing much of note happens, also makes the audience aware of the passage of time. As my wife noted, it looks like a film that any director could replicate. Yet Delphine Seyrig conveys so much meaning without saying anything at all in her role as Jeanne that it’s tour-de-force of acting and Akerman deserves credit for getting that performance out of her. Even without any additional twist, I think forcing the audience to spectate and contemplate the quotidian chores of an ordinary housewife makes for a powerful artistic statement in the history of cinema.

But of course the question of sex is central to this film and what undoes the carefully constructed routine of Jeanne’s life is experiencing an orgasm. I’m not a fan of how subtly it is hinted. Sylvain’s questions are a vital clue but it seems so artificial in how they are inserted into the narrative. But by the final scene, there is no doubt that she feels something from the sex and she does not at all like how it disrupts her life. By now, there is a wealth of critical commentary and analysis of what this is supposed to mean. A feminist might say for example that it suggests that any sort of sex work, no matter how voluntary or how safely it is carried out, is harmful to the woman. Another might say that it breaks down how she compartmentalizes her feelings which she needed to carry on with her life day after day. Certainly there is some truth in every one of these interpretations. My wife argues that the film wouldn’t have been voted to be among the greatest films ever made without that literal climax. Personally I feel that it clashes somewhat with the ethos of it highlighting the ordinary life of a housewife as something that is in of itself worthy of cinema.

I’m not sure I would consider this to be the absolute greatest of all time if only because it doesn’t specifically resonate with me but I can agree that it’s a masterful work and has influenced those that came after. As I watched it, I kept thinking of the even longer Sátántangó which tries so hard to convey pathos through its ceaseless narration. Here Jeanne Dielman achieves much the same thing with no narration at all and so feels much more authentic simply by having the character sit around doing nothing. This isn’t a particularly beautiful film and it does demand a great deal of patience. But there is no doubt in my mind that Akerman set out to make something completely different and new and in succeeding so brilliantly, proved herself to be a true artist.