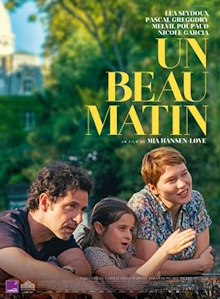

I haven’t seen many films by Mia Hansen-Løve and I’m mostly ambivalent about the last one Bergman Island. I was discomfited at first by how this one flits from scene to scene without dwelling on any given moment for very long but I soon grew to appreciate how it paints a broad portrait of the main character’s life. In fact, the style reminded me of the director’s even earlier film Things to Come and I realized that both are deeply drawn from her real-life emotions and experiences with her parents. The focus here is on the father character’s drawn out decline from a rare variant of Alzheimer’s disease. It is complemented by the story of the main character’s embrace of love at a later stage in life, an unusual combination that nonetheless works very well.

The widowed Sandra lives in Paris, works as a translator, and raises an eight-year-old daughter Linn on her own. She often visits her ailing father Georg who used to be a philosophy professor but is losing his sight and his mind to a neurodegenerative disease. While visiting the park with her daughter, she runs into an old friend of her husband, Clément. Though married with a son of his own, his work as a scientist sends him on extended expeditions, causing him to be distanced from his wife. Soon afterwards, Sandra’s mother Françoise who has divorced Georg twenty years ago, explains that his condition is worsening and the family will have to send him to a nursing home. Together with Sandra’s sister Elodie, they grapples over the costs, the suitability of the home and what to do with his possessions, especially his large collection of books. Meanwhile Sandra begins an affair with Clément after visiting him at his office. Theirs is a passionately physical relationship as they make love every time they meet, but Clément feels conflicted about betraying his wife and Sandra herself eventually grows tired of being the mistress. As he is moved from a hospital to a succession of homes, Georg’s condition continues to deteriorate until he is unable to recognize Sandra and only asks after his girlfriend Leila.

This then is an entry into the already substantial canon of films about losing parental figures to Alzheimer’s and similar diseases. Hansen-Løve’s story however in drawing from her own personal experiences with her mother, supplements this with other details of Sandra’s life even as she grieves for her father. Her career as a translator and interpreter seems solid if unglamorous, she is a great single mother for Linn, and her relationship with Clément proves that she can find love again in middle age. The general impression is that life for Sandra goes on amidst her grief and this doesn’t in any way diminish the love she has for her father. As she observes with brutal honesty, she feels more connection with his books than the broken shell of a person he now is. The books that he loved so much, written by the greatest minds and philosophers in history, encapsulate his true self as a fiercely intelligent and cerebral thinker. That his body remains alive is only incidental as she considers his mind to be long gone. The most visceral expression of distress in the film is when she begs Clément to promise that he will have her euthanized if she is ever diagnosed with the same disease before the symptoms take hold.

I also love how this film so casually evinces European social mores and values. Sandra of course is the mistress in her relationship with Clément and is later dissatisfied with it, but more because of the impermanence of the situation than any moral objection. Françoise readily admits that she hated her marriage with Georg that she blanked those years out of her mind, including her memories with her daughters, in favor of her working life. Of course they’re still responsible people who fulfill their obligations. Françoise assists her ex-husband in his infirmity, both Sandra and Clément seem to be genuinely great parents to their respective children. Yet they also don’t hold back from pursuing their passions, from embracing love wherever they might find it. As Clément simply says, life is short. I found it illuminating that Bergman Island similarly involved a cheating relationship that is held up as authentic passionate love. This also reminded me of the attitude to life we’ve seen in The Worst Person in the World. I can’t imagine an American film articulating such views.

The inclusion of so many throwaway details, such as Sandra’s daughter taking to limping for psychological reasons, suggests that these stories are drawn from Hansen-Løve’s real life. Certainly the few lines from the rough manuscript of Georg’s supposed autobiography actually came from her own mother. The messiness of this narrative contributes to its sense of authenticity and the underlying theme resonates with me much more than a tribute to Ingmar Bergman.