As an aspiring writer herself, my wife is always drawn to movies about writers. Since this film is a biography of one of the most prominent female writers of early-20th century China, it was on my wife’s radar long before its release. She was very pleased to see it being played in Malaysia, even if only in a select few theatres. When we first entered the hall, it was empty so we believed that we were the only ones going to watch it. But actually around a dozen people in all turned up, so it seems that there is at least some audience for serious dramas of this type among Malaysians.

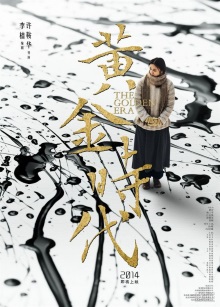

Directed by Ann Hui, herself probably the most prominent female Chinese director today, The Golden Era chronicles the life of Xiao Hong who was only 31 years old when she died. Though born to a family that was apparently wealthy enough to give her a decent education, she was unhappy at home and ran away to avoid an arranged marriage. This sent her down into a spiral of penniless misery that culminated in her plight being discovered a group of writers. One of them, Xiao Jun, helped save her from being sold to a brothel and thus started her on her path to becoming a writer herself.

One interesting technique that the film uses is to have characters break the fourth wall to directly provide expository background to the audience. Some shots are straight up interviews, others have the characters going about their lives, stop themselves and then smile and address the camera directly. It felt odd at first but I grew to like how it gives information in an unambiguous manner while also acknowledging areas where the historical record is patchy. It feels like an honest attempt to avoid sensationalizing events. I’m sure it also helps to provide extra information to viewers who may not otherwise know much about Xiao Hong and her contemporaries.

After watching the film, my wife told me about an interview in which Hui claimed that she wanted the film to be about more than just the tumultuous relationship between Xiao Hong (itself a pen-life adopted after she started writing) and Xiao Jun. We both agreed that whatever her intentions, she wasn’t very successful and the film is clearly much more about this, apparently quite famous, romance than Xiao Hong herself. This is all the more disappointing because Xiao Hong herself comments in the movie about how her work will be unread and forgotten but the gossip about her scandalous love life will live on forever.

It is particularly odd how little the film has to say about the impact of her work while she was alive and how she herself felt about it. Certainly other writers, including the greatest writer of the age Lu Xun, have nothing but praise for her writing but we never a sense of where she stands in society as a whole, nor do we even get scenes showing when and how the works are published. In fact, there are even hints that Xiao Hong primarily wrote because it was what drew Xiao Jun to her in the first place and she wanted to ensure her place in his heart, which feels like an unworthy goal. Another example is how the Hong Kong scenes seem to imply that she was either miserable or deathly sick the whole time when in fact she lived for two years there and wrote and published her best known work Tales of Hulan River during this time.

Despite what I think is a misplaced focus on the director’s part, this is a film with subtle, multilayered meanings. My wife and I had fun trying to figure out what the title itself refers to. Xiao Hong herself uses it to describe her time spent in Japan, a personal golden age of wanting for nothing materially, but a gilded cage nonetheless. But it could also refer to the time they lived in, a time of great change for China and therefore a great time for writers to make their names. I really liked the way the film depicts how Xiao Hong, after enduring a lifetime of hardship, yearns only for peace and security, while everyone else was all fired up to fight against the Japanese. I also appreciated how the film isn’t just misery porn, even if the final sequences in Hong Kong did go on for a bit too long.

Acting-wise, Tang Wei stands out and proves that her performance in Lust, Caution was no fluke. Having the camera focused on her face while she is dirty, disheveled and without makeup and having Xiao Jun comment that she is the most beautiful woman in the world is far too on-the-nose for such a veteran director, but the actress still manages to pull it off. It is especially notable how she manages to combine both ferocity and fragility in a single character. The supporting cast is also more than competent, though I suspect only Chinese audiences will be able to fully appreciate the casting choices.

Knowing nothing about Xiao Hong and the other writers of her circle, I am certainly not the intended audience of this film. Nonetheless I was able to enjoy it both as an emotionally powerful drama as well as an intriguing introduction to this literary world, but I’m not sure how true this will be for international audiences who know even less Chinese than I do. Actual fans of Xiao Hong will no doubt get more mileage out of it, though I wonder if even they will be disappointed by the lack of focus on her literary works.