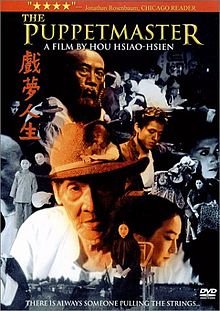

Hou Hsiao-Hsien is one of the three great directors of Taiwanese cinema and The Puppetmaster is the first film of his to be featured in this blog. It is however generally considered the second part of a loose trilogy of films about the history of Taiwan. The first one was A City of Sadness, starring Tony Leung Chiu-Wai. We’d watched it not too long ago and liked it, but that was before I’d started writing a lot about movies on this blog.

This one tells the apparently autobiographical story of Li Tian-Lu, a famous puppeteer. The man himself appears in the film as the narrator. Beginning with his childhood in the early 1900s, it recounts his trials and tribulations throughout Japan’s occupation of Taiwan, ending with the Japanese surrender following the Second World War. There’s no central plot thread tying the film together or any overall theme apart from the casual observation that Li’s stage performances are a metaphor for life itself. It’s just the story of one man’s life during what is admittedly a tumultuous period.

Considering that this is shot in the same style favored by many Taiwanese directors: static frame, camera distant from performers, absolutely no close-ups and the lack of any real excitement in the story whatsoever, it’s understandable why quite a few people think that watching this is a trying experience, if not a downright boring one. It doesn’t help that the film skips unpredictably between different episodes in Li’s life and there is always a sense of disorientation at the beginning of every scene as you try to work who these characters and how much time has passed since the previous scene.

But I think that watching this as the story of a single person’s life and trying to find something of interest in it is missing the point. This film isn’t so much about Li’s life specifically as about the era that he lived in. It’s best to think of The Puppetmaster as a portal through which you can immerse yourself in and experience the Taiwan of a bygone age. Every detail of the film feels so authentic that it seems almost unbelievable that it was made in the 1990s and not actually composed of period footage. The use of street puppeteering as a popular form of entertainment, one that no longer exists today, is the most obvious example. Much more subtle and fascinating are all of the little customs and rites shown in the film, beginning with how Li is taught from childhood to call his father “uncle” in order to sidestep a fortune teller’s prediction of a life plagued by bad luck, as well the little bits of folklore that will be dismissed as superstition today.

While watching this, my wife commented on how resolutely the camera refuses to close-in on faces, even during moments of strong emotion, as if the characters were unimportant. The contrast with Western films which dwell for minutes at a time on an actor’s face to capture every little nuance of expression is unmissable. Most obviously, this reinforces the idea that this is a film about the period in question rather than any people in particular. Another interpretation is that this reflects the greater emphasis on collectivism as opposed to individualism in Eastern culture. Indeed, familial ties are a recurring theme in this film. Characters are always seen making efforts on behalf of family members rather than themselves. There is certainly no place here for individual hopes and dreams.

Another illuminating aspect of this film is how it depicts the relationships the Taiwanese have with the Japanese. Taiwan was no paradise and they had to endure rationing and other forms of privation throughout the conflict. But it strikes me how Taiwan had a much kinder experience of the war than pretty much every other Asian country. Taiwan was never invaded and didn’t seem to see much violence. Li himself, despite having to undergo some hardship when outdoor puppet shows were banned, seemed to do quite well under the Japanese and admits to freely agreeing to perform propaganda shows for them because of the excellent terms of employment they offered. This is another way that Taiwan is unique in its relationship with the Japanese compared to all other Chinese-speaking territories.

The only thing I find missing here is that there is no depiction of joyfulness in any way. The birth of a child is relayed in a minimalist manner. Li is clearly talented at his job but is never seen to actually enjoy doing it. Strangely, the only hint of personal happiness on Li’s part is his short-lived extramarital affair with a popular prostitute and that is tempered by the fact that it is socially unacceptable and therefore must be temporary. In the meantime, many characters grow old, fall sick and many die, in an endless succession of tragedies. Perhaps this is just a reflection of the difficult times Li lived through. But I suspect that this is also because Hou felt that happy scenes would detract from the seriousness of the film and perhaps even stems from a mentality that enjoyment of life equates with decadence.

In any case, this is an incredibly dense and educational film that will yield rewards only to the patient viewer. It’s an impressive demonstration of how a great director can transform the ordinary stuff of everyday life into a gripping cinematic experience and should be required watching for anyone with any interest in Taiwan.