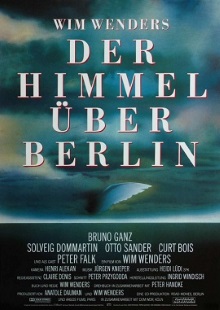

This is the second film we’ve watched by Wim Wenders and while it also stars Bruno Ganz, it really couldn’t be more different from The American Friend. It was made a decade after the other film but actually looks and feels much older partly because most of the scenes are shot in black and white and partly due to its style and subject matter.

Ganz is Damiel, one of the many angels who roam the city of Berlin at will. Except for the occasional child, the humans who inhabit the city can neither see nor hear them. The angels can hear the innermost thoughts of the mortals and though they cannot directly influence their lives, they try to offer what comfort that they can. It emerges that Damiel, having spent hundreds or perhaps even thousands of years observing life the Earth without being able to partake in it, yearns to be a mortal and falls in love with a trapeze artist. At the same time, the actor Peter Falk, playing a fictionalized version of himself, happens to be in Berlin so Damiel and his fellow angel Cassiel spend some time observing him.

This is one of those films that are thin on plot but heavy on mood and atmosphere. There is little dialogue but plenty of monologues in the form of the thoughts of the various characters. An example of this is the recurring lines from the poem Song of Childhood about children not knowing that they are children by the film’s scriptwriter Peter Handke. This dream-like sensation is heightened by the use of black and white scenes to denote how the angels seem to spectate upon the world at a remove, as if they were remote and impersonal observers. The first time that the film switches to color, for scenes in which no angel is present, is a huge shock. Though the color scenes appear more vibrant and alive, I’m struck by how they also seem more mundane and less dramatic. It’s a fantastic technique to differentiate between the timelessness of the angels’ perspective and the way that mortals exist in the here and now.

As a mood piece, it’s hard to point out any specific moments that are particularly outstanding. The whole film just flows extremely well through a combination of powerful imagery, narrative voices that are reassuring to the ears and thoughtful if not always very substantial writing. I loved all of the little acting flourishes such as the hand and head movements that create ambiguity about whether or not the humans can sense the angels as they invisibly brush hands and clasp shoulders. I also appreciated that even as the angels walk through the city, they’re not just seeing Berlin as it exists in the present and the people living in it now but also as it existed in the past and the people who were once there but are now long gone.

I’m not of a big fan of the arc in which Damiel falls in love with and pines for a mortal. There’s something creepy about him invisibly hanging around her as she lies in bed half-naked. But I can feel for the appeal of his longing for the visceral quality of human experience, of tasting coffee on your tongue and feeling the wind in your hair and hearing the crunching of dirt under your feet. I also found it odd that the angels never seem to witness any acts of outright evil. Most human interactions that they observe are amicable and the saddest bit is when Cassiel fails to stop a young man from committing suicide and is therefore experiences anguish. The film does end with a “to be continued” note and indeed a sequel was released in 1993. Since it supposedly follows Damiel as a human, perhaps it will touch more on the tragedies of being mortal.

Still, despite the somewhat trite romance this is undeniably a cinematic tour de force. Immersing yourself in the existentialist flow of the film is an incredibly moving and unique experience. As an aside, here’s a hot tip: angels apparently love to hang out in public libraries.