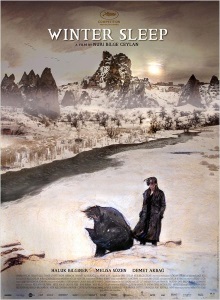

I’m pretty sure that I got this from the exact same list as Jauja and both films were winners at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival. That’s where the similarities end though since both my wife and myself found this to be fantastic. This one is a Turkish film directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan and is the first Turkish-language movie that I’ve ever written about in this blog.

Set in the popular tourist region of Cappadocia during the winter, the story is centered around Aydın, a wealthy retired actor who owns a boutique hotel in the village. As my wife notes, the film has almost no plot of speak of, being a portrait of Aydın and his relationships especially with his much younger wife Nihal and his sister Necla who lives with him. Other characters include the tenants of one of Aydın’s many properties who have been behind on their rent, Aydın’s friend Suavi who is a farmer and landowner, and his ever present and faithful assistant Hidayet who drives him around and manages the hotel.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t plenty of things going on. The imam who is the sole breadwinner of the tenant family is obsequious and wants his nephew to apologize to Aydın for breaking the window of his car with a thrown stone. It turns out the young boy is resentful that Aydın’s agents have sent bill collectors to repossess the family’s fridge and television and the police had beaten up the boy’s father, the unemployed Ismail, when he resisted. Meanwhile Aydın discovers that Nihal has been organizing a fundraiser campaign for the local schools with several other people from the village without his knowledge, but earns only Nihal’s resentment when he tries to insinuate himself into the proceedings.

All this and more is related through the lengthy dialogues that fill out this film, which running at more than three hours was apparently enough to tire out some of the judges and critics at Cannes. The film naturally makes the most of the natural surroundings it is shot in and even the interior spaces look and feel incredibly cozy and attractive, especially with how cold the village looks. But the really amazing thing with this film is the dialogue. In most other films, having nothing but two people speak in a scene for as much as a half hour at a time is a recipe for boredom, but the dialogue here is mesmerizing. Part of this is certainly due to how expressively the actors, especially lead actor Haluk Bilginer, deliver their lines but I’m more impressed with how insightful the writing is. You can sense so many things going on under the surface and so many threads of meaning in each conversation. The characters aren’t just speaking to convey their thoughts, they’re defending their pride, seeking to hurt the other party, trying to score a point and so forth. It feels so naturalistic that my wife commented that they argue in exactly the same way we argue in our own life.

Through these interactions, we see that all of the characters have complex, realistic personalities. Aydın considers himself as the benevolent leader of his little community and while he grapples with some guilt about how wealthy he is, he essentially sees himself as being both wise and sympathetic to the poor. Yet as the audience quickly discerns, just about everyone else finds him to be insufferably arrogant and condescending. Similarly, when his sister Necla starts espousing her new philosophy of accepting evil from people without retaliating in the hopes that it will kindle remorse in their hearts, it comes as a shock. Yet we quickly learn that it applies only in the context of her getting back with her abusive ex-husband in Istanbul. When a servant breaks her favorite glass, it simply doesn’t occur to her to apply her new-found philosophy to the situation as she considers deducting the cost of the expensive and rare glass out of her servant’s meager salary.

The rich and the privileged here aren’t mustache-twirling villains and the things that they say aren’t completely unreasonable. This of course is what makes the critique presented in Winter Sleep so incisive and insightful. The horror isn’t that they’re actively malevolent, it’s in how far removed they are from the everyday lives of the poor. When Aydın tries to explain to the imam Hamdi that sending the bill collectors was simply a mechanistic process intiated by his agents without his knowledge and that he didn’t even know that they were his tenants, far from making him seem sympathetic, it only heightens his indifference and his refusal to see the poverty before his eyes. Aydın’s hotel looks like a tiny piece of rich and developed western Europe, with the posters of classic films on the walls and the Apple laptop on his desk on which he writes editorials pontificating about life, culture and even religion. As his sister points out, there’s something fake in this when he hasn’t stepped into a mosque in years and knows almost nothing of the lives of the local people. When he speaks with the foreign tourists who are his customers, he treats them essentially as peers worthy of respect and politeness while he seems unable to avoid unintentionally denigrating and even insulting the impoverished locals in all sorts of petty ways.

The rich themes of the film echo back and forth with impressive skill and subtlety. Ismail’s stubborn defiance can be interpreted as a twisted mirror-image of Necla’s philosophy: accept no good from those who are evil so that their conscience can never be assuaged. When Ismail’s son Ilyas tells Nihal that he wants to be a policeman when he grows up, we all know why without him having to break his sullen silence. For these and all of the other reasons I’ve written here, I think this is one of the best films I’ve watched this year and that Winter Sleep surely deserves to be hailed as a modern masterpiece.

One thought on “Winter Sleep (2014)”