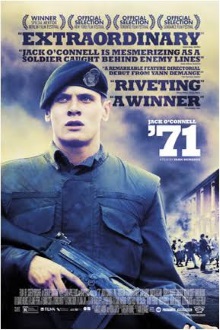

This film has been on our watch list for a while as it is considered one of the most notable releases of 2014 so watching it now is a complete coincidence. Still, seeing it just after the Brexit referendum makes for a particularly poignant reminder not to take the national unity of Britain for granted. It’s the debut work of its director Yann Demange and as you should guess by now it’s a take on the Northern Ireland conflict, focusing on one particular night in 1971.

Gary Hook is a young recruit in the British Army and his first deployment is to Belfast. As his superiors state, it’s a perfectly safe assignment since he isn’t even being sent out of the country. His unit is ordered to support the Royal Ulster Constabulary while they search the houses of suspected Irish militants for weapons and Hook is shocked at the degree of brutality employed by the police. A large crowd of Catholics soon gather to protest their actions and grow increasingly violent when it becomes clear that the soldiers have been ordered not to open fire. Hook becomes separated from his unit when he is ordered to recover a weapon snatched by a young Irish boy in the middle of the confusion and his inexperienced Commanding Officer orders a retreat. Injured, unarmed and knowing next to nothing about the situation, Hook is left to fend for himself in the middle of a warzone between the Irish and the Unionists.

Right from the scene in which the soldiers first enter the front lines of the conflict with its debris strewn and deserted streets, with makeshift barricades blocking intersections and the flaming hulks of cars scattered here and there, it’s clear what kind of imagery the director is going for. This is Belfast as post-Saddam Hussein Baghdad and the realization that it existed right in the middle of civilized Western Europe is a profoundly shocking one . This is hostile territory even if the British troops don’t yet realize it and the shit is about to hit the fan. It’s not a particularly original take but it works fine. A great moment is when the lost unit is beset by Irish children throwing water bombs filled with piss at them. The soldiers respond with disgust but are good-humored about it. It nicely captures just how clueless the soldiers are about the depth of hatred felt by the Irish towards them and how seriously they take their grievances.

Post sunset, ’71 morphs into another readily recognizable setting, that of Black Hawk Down as Hook attempts to evade IRA gunmen while navigating the unreliable allies that are the Protestant Unionists. The action is suitably tense and frenetic as Hook hurtles from one peril to another, with even the moments of apparent safety in between turning out to be deceptive and full of treachery. It does lose some points for being so obviously inspired by the prior film but worse is how all of the forces hunting for him, the IRA, the Unionists, his own unit, conveniently converge on his location for the climax. There’s a farcical quality to this that is unworthy of a serious film. Also awkward are the scenes of Hook bonding with his much younger brother, with the difference in their ages making it look more like a father and son relationship. Those scenes are too sentimental and too weak, especially given how much of a blank slate Hook is while interacting with everyone else.

’71 isn’t a bad film. It’s just that it’s closer to being an action movie than a serious one. A situation as complex as the one it tries to portray involving the complicity of the British government in the terroristic actions of the Unionists and the sense that both sides are equally villainous deserves a more sophisticated treatment than ’71 is capable of delivering. Still, it’s a decent watch and once again the impending historic event that is the British exit from the European Union is a timely moment to remember the Troubles, given how instrumental the EU had been in ending it.