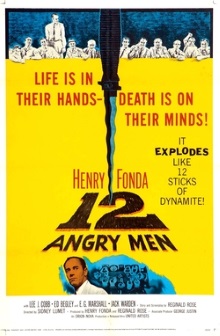

Courtroom dramas seem to be a dead genre these days, especially in the United States. My guess is that the really interesting and precedent-setting cases are just too complex to be put on film while simpler cases about street crime has to contend with the cynicism of modern audiences that the justice system actually works. In any case, 12 Angry Men is widely considered one of the best exemplars of this genre and so it was put on my list.

A young man is on trial for the murder of his father. All of the evidence has been presented and the presiding judge warns that as the crime carries a mandatory death sentence, a verdict of guilty will certainly result in the accused being executed. The jury to twelve men retires to deliberate. At first it seems like an open and shut case with the boy’s guilt being obvious. An old man living in the same building claims that he heard the boy arguing with his father and that he saw him fleeing the apartment. A woman living across the street claims that she saw him through the window stabbing his father. One juror however, played by Henry Fonda, insists that it isn’t right to send a man to the electric chair without due consideration. At his lead, the others slowly suggest reasons why the evidence isn’t quite as rock solid as it seems and that there is reasonable room to doubt that he is guilty of the crime.

The entire thing takes place in the meeting room and none of the jurors are named. They refer to each other by their juror number. None of the other characters are named either. The accused is simply called the ‘boy’. The witnesses are called ‘the old man’ and ‘the woman across the street’. Yet this doesn’t mean that they lack characterization. There’s a stock broker who believes that the cold facts point unerringly towards the accused being guilty, a garage owner whose decision is plainly driven by his bigotry, a watchmaker from Europe who doesn’t have a complete mastery of English vocabulary yet makes an effort to be grammatically perfect, a salesman who just wants the whole thing to be over as soon as possible so that he can go to a ball game and so forth. I’m amused that there’s even a juror who could have walked off the set of Mad Men: a well-groomed, good-looking advertising executive who is prone to catchy wisecracks but proves indecisive and may be the least wise of the bunch.

On one level, 12 Angry Men plays out like an exercise in logic and observation. Juror No. 8 (Fonda) reenacts the old man’s movements to prove that he could not have moved quickly enough to make it to the door to see the boy rushing out. The elderly Juror No. 9 notices that the stock broker rubs his nose in the exact same manner as the lady across the street, leading to the conclusion that she habitually wears glasses and so could not have witnessed the murder as she claims. It’s not quite fair as the jurors continuously call on information unavailable to the audience but it is impressive. On another level and this is why this film is so good, it also shows that being impartial and fair in the pursuit of justice is difficult. Tempers simmer in the meeting room even as the jurors complain about the heat. The arguments become personal as the jurors question each others’ motives for voting one way or another.

Of course this setup is still terribly unrealistic. It beggars belief that everyone is ultimately amenable to reason and everyone honestly believes in justice. Seen through modern eyes, it’s also somewhat disquieting that the jury is composed entirely of white men and no one even thinks to question whether or not that is a fair representation of the peers of the accused. Still, allowances must be made for the fact that this film was made in the 1950s. Seen in that light, It feels way ahead of its time and I really appreciated how it steadfastly holds on to the principle that the standard is reasonable doubt, so that it is better to let a guilty person go than to convict an innocent one. Even juror no. 8 readily admits that he doesn’t know if the boy is guilty. just that there is a reasonable room to doubt that he isn’t. I find that incredibly courageous both in the moral sense, as mobs out for justice are so bloodthirsty in their righteousness, and in the intellectual sense, as this isn’t exactly an issue that captures the imagination of the average cinema-goer.

It was only after the film ended that I realized that this was made for Sidney Lumet, the same director who was responsible for The Pawnbroker, another film that I felt was far ahead of its time and very unlike other American films of the era. I recently read that one of greatest injustices of American cinematic history is that while Lumet was nominated for the Academy Awards several times, he never won even once. After watching this, it’s easy to agree.

One thought on “12 Angry Men (1957)”