After months of playing this, I’m think I’m finally ready to put it down and write a post about it. I’ve since clocked well over 200 hours on it according to Steam, well above anything else except Skyrim, and I still haven’t come close to doing anything. I’ve gone everywhere with probes, landed Kerbals on the major, easy to reach planets and moons, and set up some cool orbital and surface bases. But I’ve barely played around with space planes, I’m never going to send Kerbals on a one-way death trip to Eve and the very thought of trying to grab an asteroid in solar orbit and bring it back to Kerbin fills me with chills. Even so I think I’ve gotten more than my money’s worth and I’m stopping here before it sucks up all my life.

I think that a game this well known shouldn’t need an introduction, but just for the sake of completeness, here’s one. As its title states, this game puts you in charge of a space program. You can play either in a sandbox mode, which gives you unlimited resources and a completely unlocked tech tree or the more challenging career which forces you to work your way up from nothing. You get to design your own spacecraft and then launch them in order to complete contracts. The objectives start with simple ones like just getting off the ground to breaking past the atmosphere to achieving orbit around your home planet. This earns you cash and a trickle of science points. More science points are earned from performing experiments in a variety of situations. Measuring the temperature while in orbit for example earns more science points than doing it on the ground, but there’s a cap to how many points you can earn from the same experiment in the same context so you can’t just repeat the same ones endlessly. Science points are spent to unlock more parts to build with, leading to more complex contracts, ranging from landing on the Mun to building bases in the most exotic corners of the solar system.

One of the design flourishes that make this game pure genius is that it’s not set on Earth and it’s not humans. Your home planet is called Kerbin and your people are called Kerbals. The system is in effect a miniaturized, toy version of our own real one because replicating everything at a realistic scale would make for a very tedious game. There are recognizable equivalents of many solar system bodies, so there is a Mun orbiting Kerbin and the red planet Duna is clearly based on Mars. But there are also bodies that have no real world analogues. Kerbin for example has a second moon in an orbit much farther out from the first one called Minmus. An even more important simplification is that your Kerbals require neither air nor any other kind of consumable to survive. You can plop them anywhere, on the surface of, say, Eve, the Venus equivalent planet, and they’ll stay there indefinitely until you deign to send them a rescue ship.

This doesn’t mean that the game is easy. Even without these complications, rocketry turns out to be complex enough to hold your attention for a long, long time. You’ll need to grapple with staging, i.e. dumping parts of your craft such as empty fuel tanks, at the appropriate times to improve fuel efficiency, you’ll need to ensure that your rocket is properly balanced so it doesn’t keep flipping over, you need to worry about being aerodynamic enough so that you’re not wasting energy and potentially overheating your ship by colliding too hard with the air and so on. Going up is probably the easy part too, coming back down safely you’ll have to ensure that your craft doesn’t burn up on reentry and that you don’t pop your parachutes too early or else it’ll get torn up by wind forces and the heat.

Then there’s the whole field of how you maneuver once in space. There’s a cool XKCD comic that shows how much orbital mechanics this game teaches you and let me say that it is absolutely apt. I consider myself a big fan of science-fiction but I never really understood how space travel works until I played this game. Playing this internalizes so many lessons that it’s impossible to list out everything. Some of my most important realizations include: in space everything is orbiting something and getting from one place to another means manipulating the shape of your orbits; orbital speed in lowest at the apoapsis, or the highest point of the orbit, and highest at the periapsis, or the lowest point of the orbit, this is hugely important in many contexts; making maneuvers to change the shape of your orbit, such as changing the inclination of your orbit, is expensive when you’re in a tight orbit and cheap when you’re in a very wide orbit.

I confess that I went easy-mode pretty early on and installed the Mechjeb autopilot mod. This is partly because I found that I enjoyed building different craft for different mission profiles much more than manually flying them and partly because I think the native game tools aren’t precise enough. Manually manipulating and editing the maneuver nodes is a real pain and the game is really bad at estimating how long you need to burn to achieve your target delta-v. Manually flying each craft into Kerbin orbit also gets really tedious after several dozen launches and heaven forbid you need to stay at the computer to watch over your ship while it performs a 15-minute burn. But it’s also because after a certain point, the mechanics get too complex for me. I’ll be darned if I have to figure out interplanetary transit windows by myself and what angle to burn at to get to other planets.

One of my favorite things about this as a game is that you might assume that it gets repetitive quickly but you would be wrong. After all, once you learn how to enter orbit and transit to another planet and then land there, isn’t it the same for every other body? It turns out that no because the game keeps throwing unexpected curve balls at you, particularly if you don’t understand the orbital mechanics perfectly. For example, after successfully visiting Duna, I tried a mission to Moho, the game’s equivalent of Mercury. Getting into the planet’s sphere of influence was simple enough but then I was shocked at how much delta v I would need to spend to get into an orbit around it. This is because Moho’s orbit around the sun is elliptical rather than circular and so it’s orbital velocity varies depending on where it is on its orbital path. If you happen to encounter it while it’s moving very fast around the sun, you naturally need to burn a lot more fuel to circularize into an orbit around it.

I can cite plenty of other examples, like how getting an encounter with Gilly, a tiny moon of Eve, is unexpectedly difficult due to how small its gravity well is relative to its parent; or how putting a satellite into synchronous orbit around Duna is crazy hard due to how its own moon, Ike, is also in a synchronous orbit. The upshot is that there are tons of very interesting gameplay challenges, all of which emerge naturally from the properties and positions of the planets you want to go to. Achieving milestones like landing on the Mun for the first time or figuring out a plan to land a rover on Eve and successfully carrying it out is as tense and satisfying as any boss battle in any action game.

The game’s biggest flaw is probably that it lacks a full suite of tools and features needed. Happily, this is where the mods come in. I initially tried to play it unmodded but quickly gave up after landing a rocket on the Mun by hand. Unbelievably, the default UI only provides you with a true altimeter, how high you are above terrain, as opposed to how high you are above the curvature of the body, while in first-person view inside a command pod. That’s why a mod like Kerbal Engineer Redux is near essential in order to provide you with all this information at all times including automatically calculating how much delta v you have at each stage of your ship. I also find career mode to be impossible without Kerbal Alarm Clock. The main thing is does is exactly what it says, create customized reminder alarms that go off at specific times. You may not get how useful this is until you have over a dozen missions going on at the same time. With all of your ships waiting for various reasons, for an interplanetary transit window to open up for example, or waiting for the right point in their trajectory to maneuver, or waiting to arrive within the sphere of influence of another orbital body, at which point you can give them new orders, you’ll quickly go crazy without this mod to keep track of everything.

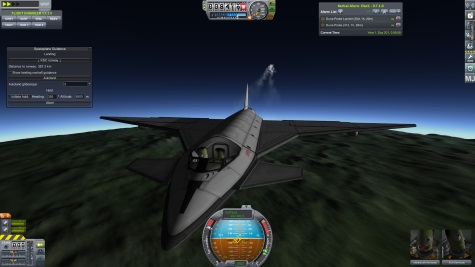

As I’ve said, there are still tons of stuff I haven’t done and I found myself continually surprised by the variety and the imagination involved in the contracts on offer. Missions like performing surveys on your home planet can be unexpectedly difficult. I had to learn how to design and fly atmospheric planes to do those. People who like challenges will be delighted by the missions that ask you to do fly-bys of a number of celestial bodies with only a single ship and presumably no in-space refueling. Many missions make no sense to actually do and are only there for the pure challenge of it. Why would anyone want to mine ore on a high gravity body like Eve and transport it to a low gravity body like its moon? Building a space station in solar orbit isn’t that hard but you’ll soon realize what a stupid project that is given how hard a solar rendezvous is. Still there’s no end of content to do in this despite the fact that it all takes place within a solar system.

There’s a lot more that I could say but I’ll end it by stating that this is certainly one of the greatest games I’ve ever played and certainly by far the most educational one. You’ll learn lots about orbital mechanics, all sorts of new words, you’ll even learn about how planes are balanced and get lift and how you need to take into account how the burning of fuel during flight affects the weight distribution. Most of all, you’ll have fun doing all this, which is almost impossible to believe before someone had the bright idea of making a game out of rocket science.