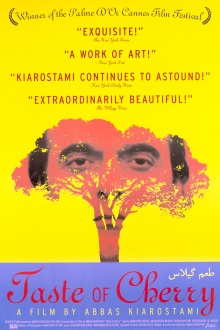

The great Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami doesn’t have a great track record with me. While I can appreciate the complexity of thought that goes into his work, most of it is either so subtle or draws so heavily from other artistic works I’m not familiar with that I find it utterly mystifying. It’s therefore quite a bit of pleasure to discover that Taste of Cherry is mostly accessible and comprehensible to me.

A middle-aged man, named Badii as he introduces himself to everyone, drives around in his truck seemingly looking for the right person. At first he cruises around in an area where laborers loiter hoping to be hired for day jobs but doesn’t seem to find what he is looking for. Eventually he spots a young solider in training, a shy boy in his late teens, who he invites into his car offering him a ride to the base he is heading towards. He says that he has a lucrative job to offer to the boy but suggests that the nature of the task might be unpleasant. The boy grows increasingly frightened and asks to be let out of the car but Badii insists on driving him to a spot where he has a dug a hole. He then explains that he intends to commit suicide but has doubts over whether or not he will actually die. He therefore wants the boy to return to the same spot the next morning to check if he is dead and if so to cover his corpse with soil. The boy immediately flees when he has a chance to do so and Badii approaches two more men with the same proposition: a middle-aged student in a religious seminary and an aged man who works in a nearby museum.

As is par for the course for Kiarostami, he thrusts the audience into a completely unknown situation with a character with mysterious motivations, forcing us to do the legwork to figure out what’s going on. The entire first act turns out to be an exercise in misdirection as Badii comes across as a sex predator. So when we finally discover his true purpose, our internal mental image of the character does a complete 180 degrees flip. It’s a bit of a gimmick but it’s a useful technique for making the audience see beyond the immediately visible. I was amused by my wife’s comment about how he likes to film a car moving back and forth along a road. In this case, the winding road he takes is an obvious metaphor for the twists and turns of life, especially as he covers the same stretches of road over and over again with each of the three different passengers who have different reactions to his decision to attempt suicide. The earthy tones of the film serves as a visual reminder of his plan to bury himself, as are the frequent shots of earth-moving machines and clods of dirt tumbling down hill slopes. The fact that the first interlocutor is a Kurd, the second one an Afghani and the third a Turk must mean something as well but that’s one I can’t figure out.

Though not exactly a wellspring of original insight, this is a worthwhile meditation on the difficult issue of suicide, dwelling especially on the doubts and hesitations that continue to plague those who have embarked on such a course. I read with amusement that Roger Ebert gave this a single star and one of his complaints is that Badii is such an enigma. We never get to learn his reasons for choosing suicide and hence this film’s treatment of the subject is necessarily somewhat abstract. It seems to me from the other works I’ve seen that this has always been part of Kiarostami’s style as he prefers to maintain distance between the subject and the audience. It makes his films more about being cerebral and thought provoking and less about emotionally moving the audience. I don’t think he will ever be one of my favorite directors as I still prefer more plot but this is a fine film and one that I am very gladly I am able to fully appreciate.