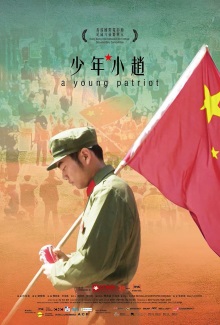

I believe that this is the first Chinese documentary to be featured in this blog and I’m pleased that it’s very much a modern one, as much about China’s coming of age as that of the young man that is its subject. It’s directed by Du Haibin who has already made several such documentaries.

The subject here is a young man named Xiao Changtong from Shanxi province. He has apparently become a minor local celebrity while still in high school due to his impromptu displays of patriotism, such as parading about in a military uniform while waving China’s flag and shouting patriotic slogans. The film follows his life for several years. In his interviews, he claims that he is doing this out of gratitude for what the Communist Party has achieved for the Chinese and angrily denies that he is being paid for these displays. Yet as the years pass and after he enters university, his attitude seems to moderate. An avid photographer, he at first participates in the propaganda unit in the university but later backs out, complaining that it is too politicized. He dreams of joining the party and enrolling in the military but admits that too many join for the sake of advancing their personal interests rather than out of a sincere desire to help the country. Things come to a head when his grandparents’ home is targeted for demolition as part of a development plan by the city government which he notes is just a front for political insiders to earn money for themselves.

To be fair, Xiao’s change in attitude doesn’t amount to a 180-degree U-turn. Up to the end, he is still a young man who loves his country and reveres Mao Zedong. One extended sequence shows him leading a group of students to be volunteer teachers for 15 days in a remote village of a hill tribe. Despite the arduous journey, uncomfortable lodgings and a language barrier, his passion and enthusiasm for imparting his love of China to the children is undimmed. Yet he does mellow out and become more cynical over time. As his university graduation draws near, he admits that he no longer wants to join the army and wants instead to earn money to gain financial security. In a fit of earlier idealism, he declares that he is opposed to drinking, smoking and playing mahjong but later indulges them. Perhaps most striking of all is that his original intention was to use his photographic skills to glorify the Chinese state, yet he ends up using them instead to protect his family’s interests against the city authorities by filming their demolition activities.

This film is never openly critical of the Communist Party-controlled China, nothing that would earn official censure in any case, but there is still plenty of ammunition against it in all manner of subtle ways. To most of us, the footage of university lecturers teaching the students that Mao’s policies and decisions, including his choice to join in the Korean War, were the best ones sounds like pure propaganda while the sight of youngsters enthusiastically repeating empty slogans feels chilling. Xiao is also an ideal subject. Obviously intelligent and highly literate, he is capable of reciting verses with admirable gusto and passable skill from memory. I especially enjoyed how he is self-aware of his patriotism in a rather humorous way. For example, he enjoys the occasional soft drink but notes in a semi-serious way that it wouldn’t look good for such foreign imports to be seen at a pro-China event. These attributes make his gradual transition highly convincing and the process itself an engaging watch.

Xiao’s story makes for wonderful cinema but it’s probably too much to hope that most of these brainwashed students will make the same transition. The subtext here is that propaganda works and many of China’s youth have been indoctrinated to a scary degree. All the same, this is a valuable documentary that makes accessible to a wider world aspects of modern Chinese society that the official media aren’t always eager to show. Even the scenes of the Maoist revival led by Bo Xilai shortly before his fall from grace are fascinating and I doubt that the phenomenon is covered in any other independent media. For all these reasons I highly recommend this to anyone who wants to know more about the intricacies of Chinese politics in the modern era.