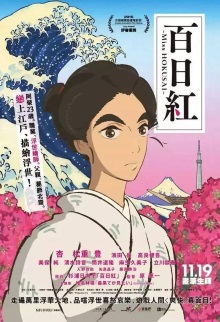

This is a Japanese animated feature that, unusually, has at least some historical basis. Like many such projects, it’s an adaptation of a manga. The central character is Katsushika Ōi, nicknamed Sarusuberi, which is the Japanese title for the film. Her father is called Tetsuzo in the film but he is better known as the famed Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. Even if you think you don’t recognize this name, I guarantee that you only have to google some images of his paintings to realize how famous they are.

Rather than having a main plot, this film presents a series of stories from the lives of Ōi, her father and one of her father’s students, Zenjirō Ikeda. The stories show that Ōi frequently fills in for her father to help him complete contracts on time without being credited for the work under her own name. Hokusai himself is an unparalleled genius who lives only for painting and pays attention to nothing else. Much to Ōi’s disappointment, he neglects the younger daughter who was born blind. Hokusai does seem to have an interest in seeking out unusual sights, perhaps as a way to gain inspiration. As such, many of the stories have a supernatural element. In one of them, Zenjirō hears of a courtesan whose head is said to leave her body and fly away at night. They meet with her and Hokusai convinces her to let them stay for the night to watch by telling a story about how his own hands used to fly away from his body and roam the world until Buddhist sutras. Due to this episodic nature, there’s no real finale either, save for text explaining that Hokusai eventually lived to the ripe old age of 90 and Ōi stayed with him until the end.

The lack of a main plot somewhat dulls the emotional impact of the film but if you can look past that, there is plenty to admire in all of the stories. I liked the ambiguity over how much of the supernatural elements are actually real even though the characters take it with complete seriousness. In the scene with the courtesan for example, Zenjirō is initially unable to perceive the flying head and the other two blames it on his lack of imagination which also makes him an inferior painter. I also liked how there aren’t clear resolutions to some of the episodes just as if they were realistic depictions of slices of their lives. A client tells that Ōi that even though her skills are technically flawless, her erotic paintings lack sensuality. He also notes that while Zenjirō isn’t as skilled, his imperfections amount to a unique style of his own and he knows women well enough that his paintings are sensual. She visits a courtesan herself in an attempt to learn more but nothing comes of it and I understand that this is a reference to how history records her as having married only very briefly once and subsequently returned to living with her father.

The art style isn’t flashy but it’s effective enough and it has its moments when depicting the city of Edo or the winter scenes with Ōi’s younger sister. There’s a strong sense of Japanese-ness that suffuses the film though I wish the film had talked more about some of Hokusai’s most famous paintings. I also note that this film seems to depict Hokusai as a seemingly poor artist who neglects the commercial side of the industry but this doesn’t seem to be historically true as he was both prolific and popular during his lifetime. Overall this is a fine film if not an outstanding one. I think it’s especially noteworthy that it focuses on the daughter rather than the more famous Hokusai himself, a choice that stems from it being an adaptation of a manga by Hinako Sugiura, herself an early female manga artist and writer with feminist leanings.