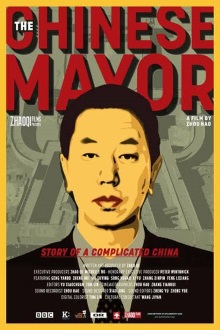

One benefit of being a subscriber to The Economist and frequenting economics blogs is that I get film recommendations like this which I doubt appear on the radar of most critics. This documentary follows the efforts of Geng Yanbo who was the mayor of Datong, a small Chinese city in Shanxi province, to transform it into a cultural and tourism center. It doesn’t seem to be very well known as it wasn’t distributed widely.

Geng is a workaholic, take-charge kind of mayor as this film shows him zooming about Datong personally overseeing everything. His major concern is ensuring the speedy demolition of over a hundred thousand illegally constructed houses dating from decades ago to make room for a rejuvenated city center around the city’s historical walls. He claims to have great veneration for ancient Chinese culture and hopes that his projects will kickstart a cultural and tourism renaissance in Datong. Naturally this upsets the owners of these buildings who tearfully protest the demolitions and Geng appears to do his best to address their concerns and ensure that they are compensated. The scenes give us a reasonable idea of what the mayor’s busy day to day schedule looks like, extending even to meetings in which he berates underlings and subcontractors for failing to perform adequately at their jobs while his wife constantly scolds him for working too hard and sleeping too little. In interviews, the then 55 year-old Geng expresses his hope that this will be his last posting and that he will be allowed enough time to bring his projects in Datong to fruition. But then the worst happens and he is suddenly assigned to another city with no prior warning.

As a film made with Geng’s full cooperation, The Chinese Mayor no doubt presents him as he would like to be seen, making it a bit of hagiography. Its bias is obvious. For example, Datong is introduced as China’s most polluted city but no further mention of this is made in the film. Similarly the focus in entirely about Geng’s aspirations and plans for the city without any discussion about why this was necessary: because the local economy depends heavily on a decaying coal mining industry. Indeed, Geng happily strolls through the new cultural buildings and listens to evicted residents about their problems, but there isn’t a single shot of him in a factory or a coal mine. As this documentary tells it, this mayor’s most serious flaw is that he works too hard to his wife’s annoyance. When he is reassigned, even those unhappy about his demolition program begs for him to stay.

With these limitations in mind, this is still a very instructive and fascinating documentary. It reveals for example that mayors in China routinely live in the military base for their own safety. My wife was surprised to note that at no point does Geng make an appeal to Communist or even socialist values. He does wax lyrical about the moral superiority of the ancient Chinese but save for a cute Mao Zedong statuette on the dashboard of his car, there are no chest thumping displays of nationalism or loyalty to the party at all. In fact, there’s even a subversive element in how it frames the Communist Party as the villain of the story. Geng bemoans that only the provincial committee, embodied here in the person of Party Secretary Feng, has the power to decide who is mayor and he himself would very much like to stay on. One extended scene shows officials being elected to their posts. However since the only people allowed to vote are appointed delegates and there is only one candidate for each position, it actually serves to look like a mockery of democracy.

We will probably never know the real reasons behind Geng’s dismissal. As far as I can tell, he remains as the mayor of Taiyuan, an ostensible promotion that suggests that he remains an official in good standing. The documentary ends with a note that Feng has since been dismissed and that Geng’s successor abandoned all of his projects, causing the city to be saddled with huge debts for no gain. Numerous articles can be found online describing how Datong is worse off than before though many still look fondly upon Geng’s tenure as mayor. Whatever the truth and whatever motivations Geng has for participating in the making of this documentary, it is an illuminating perspective on how Chinese government works on the city level. City mayors in Western countries will certainly be envious of how much real power Chinese mayors wield by executive fiat, unburdened by things like the separation of powers and the need to be subject to the rule of law.