This is the second film we’ve watched by Polish director Andrzej Wajda, the last one he made before he died in fact, and to no one’s surprise, it isn’t any less darker than Katyń. This one is a biography of Władysław Strzemiński, apparently a Polish artist of some renown beginning in the 1920s.

At the beginning of the 1950s, Strzemiński is one of Poland’s most celebrated artists, beloved by his students and respected by his peers. Despite being handicapped by having only one arm and one leg, he continues to teach at the school he co-founded and to paint. However as Soviet control over the country grows stronger, he becomes disgusted by the rulers’ insistence that all art must be in service of the socialist values of the era. When the Minister of Culture visits the school and gives a speech to that effect, Strzemiński openly snubs him. This sets off an escalating series of government moves to censure him, beginning with firing him from his teaching position and vandalizing his art exhibits. The film also shows his relationship with his daughter Nika who lives with his seemingly estranged wife, the sculptor Katarzyna Kobro. When Kobro dies, Nika initially moves in with her father, but it soon becomes clear that he is too embroiled with his troubles and his work to be in any position to take care of her.

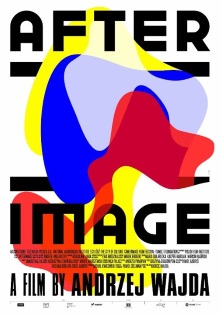

Since this a biography about a real artist, the film loses some power if the audience doesn’t know who he is. I didn’t and in fact, it took some time for me to even realize that it’s based on a real person. Wajda does a decent job of clueing us into Strzemiński’s achievements without being too expository. Scenes show his Neoplastic Room and his students’ efforts to record his theories into a book reveal some of his art philosophy. The title of the film itself is a reference to his theory of human vision. It doesn’t really help you understand his work as he is a modernist who focuses on abstract art but it does give you a good sense of why he was so important and how much his contemporaries looked up to him.

The increasing ostracism and persecution of the state towards Strzemiński is about what you’d expect, beginning with his firing and escalating to hired thugs breaking into his exhibition space to destroy his work and even kidnapping his allies and friends. It’s not new but Wajda manages to show it all to chilling effect. What is new and especially intriguing to me is how Strzemiński’s students and allies defer to him. The film’s depiction of his relationship with his daugher Nika is especially nuanced. She is well aware of her father’s status as one of Poland’s greatest artists and so supports him. Yet to do so, it is clear that she has had to learn to be independent despite still being a child. She is the one who makes sure that he eats and doesn’t smoke too much. He does love her of course and expresses regret that she would have to live a hard life but seems resigned to not being able to do anything about it. For example, there is no question of him compromising his principles and cooperating with the authorities in exchange for a decent standard of living. It’s very painful to realize that Nika herself understands this very well.

All in all, this is another excellent film by Wajda but I fear that its subject matter rather limits its audience. Unless you’re a Pole yourself or run in the right art circles, it’s unlikely that you’ll get engrossed in it.