An experimental Soviet-era black and white silent film with no plot and no intertitles doesn’t sound like a lot of fun, even if it’s only an hour long. But this film, now considered one of the greatest documentaries of all kind, may surprise you. It does start slow with straightforward shots of inanimate objects and you wonder what it’s trying to do. Then it grows in scope and the shots become more sophisticated as if the cameraman is slowly learning as he goes until it becomes a joyous celebration of everything a camera is capable of.

The film opens with the interior of a lavishly furnished and equipped but empty movie theatre. Then the audience, ordinary Soviet citizens, file in and sit down to enjoy the spectacle. The shots are unimpressive at first, being still images of machinery and objects without anything tying them together. But they gradually become more interesting and complex. You see people trickling onto the streets of the city, trains rushing past, people operating the machinery. Very often you even see the cameraman operating the camera or toting it around on its stand. There’s more motion as the camera is placed on trains and all manner of vehicles. The film experiments with special effects, superimposing one image on top of another and playing with stop motion. We even get to see the editor cutting up the film stock to create the effects. Even without the ability to record sound, we see storytelling techniques in use as people converse with one another and the camera captures the emotions on their faces. From there, it goes on to document a wide range of human endeavors: at work, weddings and deaths, sports and even a woman giving birth.

The music here plays a major role in getting us to appreciate and enjoy the images. However since the film itself is silent and was originally meant to be accompanied by a live orchestra, there are multiple different soundtracks that were made for it. I’m not even sure which one we had but it worked very well, synchronizing perfectly with the images that are often played in fast-forward. The effect is to impress upon us the wonderful expressive power of the camera and its infinite possibilities. I don’t know enough about the history of cinema to identify which particular shots or effects used here were genuinely invented by director Dziga Vertov here or taken from elsewhere but seeing them all in one place and from so early is amazing. It’s easy to imagine how budding filmmakers used the techniques and shots here as references to build their own projects. Even though there is no plot, we feel a sense of playfulness, joy and wonder from the interplay of the visuals and the music.

At the same time, this clearly serves as a piece of Soviet propaganda. I noted that for all the film strives to demonstrate what the camera can do, Vertov seemingly has no interest in turning the lens onto the natural world. So there are no sweeping shots of the landscape, no macro shots of flora and fauna, no sense of wonder about the wildlife. Instead it’s all about the glorification of man and the Soviet state. Even when it is showing dire situations such as deep underground inside a mine, it wants to overawe us by how man has tamed the incredible forces involved. That’s understandable for the context under which it was made and doesn’t make it any less impressive, but of course there’s more that the camera can do that is left out here.

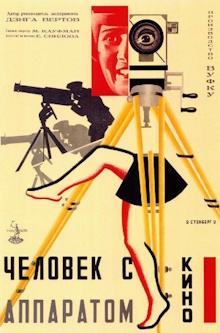

I added this to my list more out of a sense of obligation than anything in because it’s so highly regarded. But I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it once I understood what it was trying to do. I suppose it could stand to be a little shorter as there is little point in repeating a camera trick or technique once they’ve already used it once. Finally I found it heartening that this was effectively made by only three people: Vertov himself, his brother Mikhail Kaufman who is the cameraman and Vertov’s wife Yelizaveta Svilova is the editor we see. With only this, they made cinematic history.