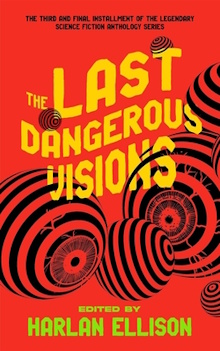

I’ve read plenty of short stories by Harlan Ellison though I don’t consider myself to be much of a fan. His novels are not considered notable and I suspect that a large part of his legacy comes from his contributions to television shows like the original Star Trek and Twilight Zone. His Dangerous Visions anthologies were hugely influential however and this final book was announced in 1973 and never came out. Ellison died in 2018 but his estate’s executor J. Michael Straczynski continued working on it and so now here it is.

To be honest, I’ve never read the previous two collections either. I have read quite a few of the stories in them from other sources and so never thought to buy those particular anthologies. I really ought to however. This is a fairly hefty volume that includes a total of 31 stories, though 8 of them are short interludes. But Straczynski’s introduction and his exegesis of Ellison’s life alone take up a sizable chunk of the book. He details his lifelong friendship with Ellison and lays out his suspicion that he suffered from undiagnosed bipolar disorder throughout his life. He attributes Ellison’s inability to put out this book despite repeated promises to his deteriorating mental state and explains that he was even addicted to buying stories, resulting in an unpublishable hundred over stories bought. Over time, multiple authors have died before their stories were published and the lateness became something of a legend and a matter of some acrimony. For at least one or two writers, this was their one and only fiction sale and that they passed away before their stories saw publication feels especially tragic to me.

For this volume, Straczynski decided to keep the best of the older stories Ellison bought and solicit stories from current generation writers to ensure that the book is in more keeping with the times, with a more diverse mix of writers. He also sent out a call for submissions from completely new writers. This resulted in the story Binary System by Kayo Hartenbaum, about a solitary human being stationed on a remote ship with an ambiguous sense of identity. I loved the setup but didn’t like that it ended too soon with no satisfying resolution. It is an appropriately-themed story by a genderqueer author. Of the other newer stories, I similarly liked the premise of Cory Doctorow’s The Weight of a Feather about a separate community of people who have been exiled for being toxic. The personal lesson it teaches that no amount of good deeds can cancel out past wrongs is well taken. But I have so many questions about how this community was set up and its governance. What I can say, I like my science-fiction stories to be about the world rather than particular characters. I also really liked After Taste by Cecil Castellucci and First Sight by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Both are great examples of science-fiction with horror overtones.

That accounts for most of the modern stories and unfortunately this does mean that I’m not as fond of the older stories. Some are okay fantasy or horror stories but don’t seem especially original. One interesting story is Goodbye by Steven Utley which tackles the unanswered question in time travel stories about what happens to the people left behind when the traveler leaves. That the timeline still exists after the time traveler exits it is alone a fascinating question of metaphysics. Yet the grief, anger and sense of betrayal here is really no different from any other form of permanent leave-taking. My favorite out of these tend to be the truly wacky ones. One example is Falling from Grace by Ward Moore, set so far in the future after the fall of civilization that human language has been corrupted. It’s such a fun read because we certainly know what the words really mean while the characters engage in all kinds of wild guessing. Other goods ones are War Stories by Edward Bryant which takes you into the mind of a man-turned-shark and Rundown by John Morissey, appropriately described in its introduction as being akin to the writing of Hunter S. Thompson.

There are several okay stories where I’d guessed what the author was going for early on and of course more are entertaining and interesting to read without blowing me away. All in all, I’d say it’s a solid, respectable anthology of stories but not an outstandingly good one. This book has been hyped up so much over the decades that no one, not even Ellison, could have delivered all that it promised to be. Straczynski did as fine a job as anyone could expect and the publication of this book brings to a close a long saga in the history of science-fiction. I enjoyed this volume for what it is worth but I suspect that I will be more impressed when I finally get around to the first two books of the collection.