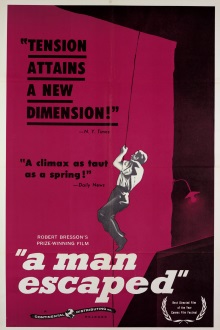

My blog posts have been full of more recent releases lately so I thought I’d go back to plumbing the back catalogue of some of the most highly regarded films of yesteryear. Robert Bresson is considered one of the greatest French directors ever but this is the first time I’ve watched one of his films. His work is cited by the French New Wave directors as one of their primary inspirations and I believe that A Man Escaped is his most famous film.

Fontaine is a member of the French Resistance imprisoned by the Germans during their occupation of France. He is determined to escape, believing that he has a duty to continue the struggle even after being caught. To this end, he is constantly on the lookout for opportunities, connecting with his fellow prisoners and examining every object in his cell to see if they can be turned into useful resources. Eventually he discovers a flaw in the wooden door of his cell and starts to wear it down, turning an iron spoon into a tool to do so. Another prisoner thinks his plan is too complicated and tries another way. He is caught but his failure provides critical information to Fontaine. However just as Fontaine has everything that he needs readied, including the hooks and ropes, he is forced into a moral quandary. A cell mate is assigned to him, a French man who has chosen to join the German army. Fontaine needs to choose between trusting him with his plan or murdering him before he escapes.

This is a tight, compact film that is entirely about the escape and nothing else. The entire plan is shown step by step in precise detail and I got a great MacGyver vibe from watching Fontaine jury-rigging the equipment he needs. For example, he strips the metal springs from his bed, pulling them into strands of wire, wraps cloth around the wire to turn it into a rope and coils another length of wire around it to keep everything in place. The film also shows the dreariness of the prison’s daily routine, trooping out of their cells to empty their waste buckets, washing up and then waiting for their one meal a day delivered in a metal cup. I found watching it to be a mesmerizing experience, both out of fascination about the internal workings of these prisons and because of the stark state of mind this induces. In interviews, Bresson commented that he was going for a pure, ascetic experience and this film certainly delivers that. There’s something almost spiritual in how Fontaine is absolutely determined to escape, as if he knows that to act otherwise would mean his spirit was broken.

Another decision in the film is one that reminded me of the recently released Dunkirk. While the prisoners are treated poorly, there doesn’t seem to be anything personal in it. The camera refuses to focus on the faces of the German guards and officers and there are no scenes of petty cruelty such as you might expect in a conventional Hollywood film. This makes Fontaine’s escape less of a battle against his captors and more of an internal struggle against himself and his refusal to give in. Indeed one of his cell neighbors is initially near catatonic, having given up all hope. But Fontaine’s efforts to escape appear to imbue new life in him even if he himself is not involved in the escape.

No doubt the intense focus of this film, showing even the tiniest minutiae of Fontaine’s actions, was a revelation for that era’s filmmakers. Still apart from the meditative quality about the duty to escape, its narrow focus feels a bit lacking in ambition. I enjoyed it quite a bit and found myself being engrossed in its intensity but its limited scope somewhat limits its impact.