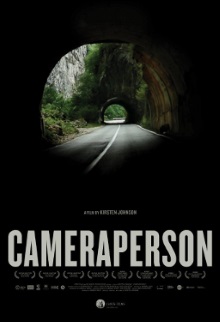

This is a documentary with an insanely high Rotten Tomatoes rating and was cited by multiple critics last year as one of the year’s best films, so naturally it was added to our watch list. It was made by Kirsten Johnson, who seems to be more of a cinematographer than a director. She asks that this film, compiled from footage of other documentaries that she has worked on plus personal videos of her and her family, be considered as her memoir.

The documentaries that this compilation draws from go as far back as the early 2000s and span quite a diverse range of subjects, including some quite famous works such as Fahrenheit 9/11, Derrida and Citizenfour. One thing that they all have in common is that none of them have been directed by Johnson herself. There is some attempt to group shots according to certain themes, such as during a succession of images of sites of massacres or noteworthy disasters but for the most part there seems to be little organization here beyond the fact that Johnson shot all of them and that she felt some special personal attachment for them. Some of the more memorable scenes for me include a midwife delivering babies in Nigeria, an attempt to surreptitiously film a prison in Yemen and a boxer in New York expressing his fury following a lost match.

One might expect a documentary about the life and career of a cinematography to be filled only beautiful images but this is largely not the case, which makes this film that much more interesting. It’s better to think of this as a collection of out-takes, bloopers and in-progress shots from her various projects. The intent is to draw attention to the photographer’s role as part of the filming process itself and how a relationship develops between the photographer and the subject even though most documentaries try to make the cameraperson invisible. Various scene demonstrate how the director or interviewer is very much an active party in every scene. During an interview of a young man injured in an attack in Afghanistan for example, he speaks at first in English, then apologizes for it as if realizing that the interviewer would prefer him to speak in the Dari language for the sake of authenticity. In another scene about sexual violence in Bosnia, the interviewer asks the woman a question and then tells her that she would reply with a specific opening line. Most of us are of course well aware that such interviews are always guided by the director but there’s something valuable nonetheless in explicitly showing this.

The film also addresses the filmmakers’ role and perhaps moral dilemmas during times of human suffering. Ironically the best example of this takes place during a perfectly peaceful scene in Bosnia. While visiting a family in the countryside, Johnson appears to notice two children playing and turns the camera on them. The older boy is idly chopping an axe into a block of wood while a much younger toddler tries to grab the axe. She audibly gasps as she realizes how easily the axe could chop right through the toddler’s fingers. Yet rather than dropping the camera and telling the parents, she keeps filming. In the end nothing happens and one could imagine that the parents are used to the children playing in this manner. Still this makes for a powerful capsule example of whether the cameraperson should intervene when he or she witnesses an ongoing or impending tragedy.

The inclusion of shots of Johnson’s family and in particular her mother as her mental condition deteriorates from Alzheimer’s serves to remind the audience that the person behind the camera is always a real person with feelings, thoughts and motivations of her own. Even if this person is never visible in the final product, the film wants to tell us that we should never forget that the choices and actions of the cameraperson always influences it.

Unfortunately I don’t believe that the film succeeds as well as the director might like. I get the philosophy and thinking behind this project and admire what it is trying to do but its execution leaves much to be desired perhaps because Johnson is a better photographer than a director. It strikes me for example that many scenes are suffused with common, everyday sentimentality that don’t contribute much insight. As such I find it hard to muster much enthusiasm or passion for this film. It’s a decent documentary but I don’t think it deserves a near perfect rating.