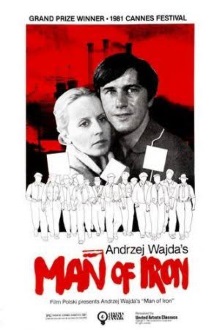

So this is the third film we’ve watched by Polish director Andrzej Wajda and this one dates from 1981, before the fall of Communism in Poland. I was aware this is the second of a duology of two films but my wife and I have limited patience for films that require deep knowledge of a country’s history and Man of Iron is the more well known work of the two so I chose to watch only this one. This did lead to some confusion about who’s who but overall it didn’t work out too badly.

It’s 1980 and the workers’ strike at the Gdańsk shipyard is in full swing. Radio journalist Winkel is ordered by the state to produce a show that smears Maciek Tomczyk, an activist who was instrumental in organizing the strikes. He is given an extensive dossier on Tomczyk by the police and does not have the option of refusing the assignment. Outside the shipyard Winkel meets Dzidka, a friend who now works at the local television network. It turns out that Dzidka knows Tomczyk since their university days and he recounts stories of their involvement in the 1968 student protests and how Tomczyk begged his father Mateusz Birkut to persuade the shipyard workers to join in but was rebuffed. In 1970, it is the turn of the shipyard workers to rise up but this time the students refused to join in and Birkut is shot by the authorities on the street. Dzidka then introduces Winkel to other people who tell more of the story including Hulewicz, Tomczyk’s grandmother, and Agnieszka, a journalist who Winkel also knows and later became Tomczyk’s wife.

As with Wajda’s other films, Man of Iron was made for Polish audiences who presumably would be well aware of the Gdańsk strikes of 1980 and the events that led up to it. Then there’s the fact that while Maciek Tomczyk’s story was inspired by that of various real life activists, most notably Lech Wałęsa himself, he is actually a fictional character. This makes it tough for non-Polish audiences to fully grasp what is going on and connect the events and characters to real ones. Still the presentation here is straightforward as even the flashbacks are in chronological order so with a bit of perseverance and looking up Polish history on Wikipedia, it is possible to get a grip on the flow of events. I like how the focus isn’t on the larger picture but how on a more individual level activists are driven to fight against the system at great personal cost to themselves and how they can make a difference.

Perhaps my favorite part of the film is that it includes characters who do know right from wrong but don’t quite have the same level of resolve as Tomczyk. When he is fired from his shipyard job, the clerk tearfully hands him the pink slip saying that she has no choice but to do so or else she would lose her own job. Winkel himself is the prime example of this: intelligent, educated and well connected enough to know the full truth, he is nonetheless too fearful to openly defy the authorities by refusing the assignment yet still succumbs to peer pressure to sign a petition in support of a free press. His intent is clearly to straddle both sides to see who comes out on top and it’s almost painful to see how his delight to see the strikers come out on top of the negotiations when they make it clear that he is not one of them. One funny flashback scene even has Winkel instantly disappearing when he realizes that Agnieszka is in the company of Tomczyk at the television station. It seems easy to look down on people who are as weak as Winkel but I think Wajda’s point here is that people like Tomczyk are the rare ones and most of us, me certainly included, would not have the courage to do what he did.

Once again I consider this an excellent film that is of immeasurable value to Poland itself and it’s impressive how Wajda within the very brief window of opportunity when censorship was briefly relaxed. However as before the very specificity of its content and how it is very much a Polish film made for Polish audiences rather limits its reach to a more international audience. Watching it can be a rewarding experience for non-Poles willing to do the extra work of learning about this period of Polish history but I suspect that some of its emotional impact will always be lost on us.