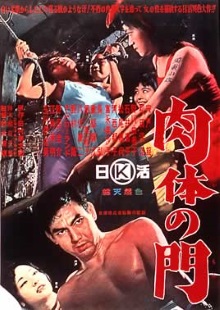

This marks the third film we’ve watched by Seijun Suzuki, surely one of the most unusual directors Japan has ever produced. Unlike Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter however this one is not about gangsters even if it does star Joe Shishido with his famous, artificially-enhanced cheekbones. Instead it’s about a group of prostitutes in Tokyo immediately following Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

Maya is a young woman who lives in a poor ghetto in Tokyo and is impoverished to the point of starvation. One day after being caught and beaten up for stealing food, she asks a prostitute Abe to show her the ropes. Maya becomes a member of their gang, staying together in a bombed out building, looking out for each other and jealously defending their territory. In particular she is taught their most important rule: they must never give away sex for free for that would ruin the livelihood of all of the girls. One day a Japanese returnee soldier injures an American GI in the local market. Named Shintaro Ibuki, he hires Abe to help hide him but is injured while escaping. He finds his way to the girls’ building and, seemingly impressed by his macho attitude and his courage to stand up to the Americans, the girls allow him to stay. Each of the girls fall in love with him in their own way and for Maya in particular, he reminds her of her brother who died fighting in Borneo.

Gate of Flesh presents a view of Japan that is so vastly different from the image of the country today that I was shocked it was allowed to be made back in the day. The streets are lined with ruins and people resort to pretty theft just to feed themselves. Throngs of Japanese women throw themselves at American GIs in exchange for a bit of money to buy some food. When a Japanese woman is raped and just left in the field, no one gives her a second thought. The consequences of being on the losing end of a war is necessarily ugly but seeing it being applied to Japan is still something else. Of course there’s plenty of US-bashing in here with the GIs being depicted as boorish monsters but the much more pervasive sense here is that of self-loathing. Shintaro is a heroic figure to the girls for defying the Americans and this particular group, prostitutes though they are, have enough pride to never accept Americans as customers. But part of his character is also his post-war cynicism and how he despises Japan’s leaders for leading them to the present disaster. He remains loyal to his comrades in war but he treats the Japanese flag with something very close to derision.

As terrible as the living conditions depicted here are, this film is not misery porn. Much of it is in fact fairly light in tone as the girls appear to still have plenty to live for. They enjoy singing and dancing in the ruined building that they share. They even have a sort of pride in their profession. At the same time underlying all this is bitterness. It shouldn’t escape the audience that there is a contradiction between Abe proclaiming to Maya that they work for themselves without any pimps and how they all fawn over Shintaro and compete with each other to give him presents when he enters their lives. I really liked the interaction between Maya and an American priest of a church to which it seems she used to be a member. The priest repeatedly begs for her to repent and eventually she tries to seduce him instead, with the implication here being that morality is all well and good but what else can she do if she is to survive? This is a hugely rich film that a good critic can mine for plenty of material.

As you might expect from the director’s other works, the presentation is rather unusual as well. On the one hand, there are some great shots of the squalid streets with lots of detail and many extras. Yet their apparently limited budget forced them to rely on painted backdrops for some key scenes and rather than trying to hide these, Suzuki instead chose to embrace the artificiality giving these confrontations a rather theatrical feeling. Plus the complexity and richness of the film’s themes sits oddly with its willingness to titillate the audience with semi-nude shots of the women. The film never really shows any onscreen sex but there is a fair amount of violence, most of it perpetrated by the girls on one of their own who has flouted the rules. Those can be unsettling to watch and feel like they belong in a cheaper, less worthy production.

All in all, I consider this to a great film, odd quirks and all. Seeing post-war conditions in Japan was a real eye-opener and the incredible complexity of its themes prove that the director, while being highly eccentric in his style, does everything with a lot of care and thought.