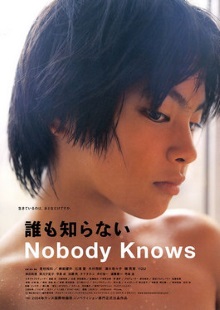

So this is another film by director Hirokazu Kore-eda and we’ve certainly watched a fair few of his works across the past several months. This is the earliest of his films yet and it’s based on a real event that took place in 1988 albeit very loosely. It’s odd now that I notice how so much of his work share a theme about parents failing their children.

A family consisting of a single mother and four children move into an apartment thought the apartment hides the existence of all but the eldest boy, Akira, from the landlord. The children do not go to school and Akira who is the only one allowed outside does most of the work in running the household, buying groceries, cooking and paying bills. The second eldest, Ayu, helps with chores at home but must be careful not to be seen at the balcony. While this arrangement works for a while, the mother’s absences become more and more frequent. Once she is absent for a whole month and Akira has to go find her old boyfriends to ask for money. It becomes evident that each of the children have a different father. Eventually the day arrives when the mother leaves and never comes back. When the money runs out, the utilities are cut and the children lack food. Akira realizes that the mother has most likely married a new boyfriend and started another family.

This is an incredibly heart-wrenching film to watch and you pretty much spend the entire time hoping that some adult will eventually notice the plight of these children and take charge of the situation. The directing and acting are both superb and it’s painful to see the once orderly household slowly devolve into a chaotic mess as the children are left to their own devices. The director once again displays his keen insight on human psychology as we see Akira’s desperate longing for some form of social contact outside of his family, how the youngest ones keep pining for the mother’s return and how the adults who do know what is going on are almost willfully ignorant. It is kind of implausible how this went on as long as it did with the landlord in particular not taking any action despite months of unpaid rent. In real life it seems that it really was the landlord who finally called in the authorities but that was only after the children had been left alone for nine months.

From a storytelling perspective, I think it’s illuminating to compare this to Shuttle Life that we watched recently as both films try hard to present a truly tragic situation. One obvious point is that the Malaysian film shoots its quiver early, front-loading its most horrific event and having the rest of the film deal with the aftermath. The Japanese film on the other hand builds up the sense of tragedy gradually, ratcheting up the tension over time. I especially like how the children here are allowed to experience moments of joy even in the depths of their despair as when the youngest girl is let out of the apartment with her squeaky shoes or when a coach invites Akira to join a baseball game. This shows that the director understands that such moments only enhance the sadness of the film as the audience understands that they are transient and unsustainable. Shuttle Life does no such thing, bludgeoning the viewer with disaster after disaster to the point of stretching credibility and inuring us to any further pain. Watching this only reinforces the sense of what an amateurish effort the Malaysian film was.

Of course this is a highly specific, isolated case, not to mention that this depiction has been fictionalized as well. Still one can’t help but be shocked that this could have happened in Japan and once again I appreciate this director highlighting this common, lived-in version of the country compared to the shiny, swanky one that we’re usually exposed to. Watching this one is hard enough that you probably need to psych yourself up for it but it’s a very worthy experience.

One thought on “Nobody Knows (2004)”