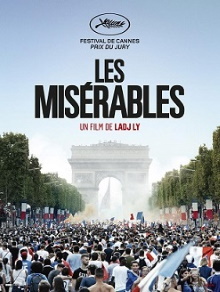

This most definitely not a musical film is the first directorial feature of its director Ladj Ly who previously made a name for himself for similarly themed short films. It immediately made waves upon its release and it’s easy to see why. Even from the very first shots, it seizes your attention with its energy and urgency and never lets up. As usual with such things, it can offer no easy solutions to longstanding intractable problems, but its revolutionary message rings loud and clear and it certainly lives to its adopted title.

On the heels of France’s victory at the 2018 World Cup, Stéphane a newly transferred police officer, is shown the ropes by squad leader Chris and team member Gwada. They are assigned to Montfermeil, a suburb outside Paris which as Chris notes was where Victor Hugo wrote Les Misérables. Nowadays it is a crime-ridden area with a heavily black population. As they drive around patrolling, the two veterans demonstrate a deep knowledge of who’s who in the neighborhood and make Stéphane uncomfortable in how they use force in violation of guidelines to intimidate the locals. Trouble occurs when a group of gypsies from a nearby circus arrive in force accusing of the local black people of stealing something from them and threatening violence. After some confusion, it emerges that what was stolen was a lion cub. The police promise both Zorro, the leader of the gypsies, and the Mayor who is the leader of the black community that they will find the lion. Thankfully this is not that difficult in the age of social media as the police know that whoever stole it won’t be able to resist boasting about it.

Since La Haine in 1995, films about the Parisian banlieues occasionally exploding into violence are an established genre in of themselves. This one distinguishes itself by mainly showing events from the perspective of the police officers, one of whom, Gwada, is himself a Muslim clearly born of immigrant parents. Yet even he is shown to be complicit in the abuse of power as there is a sense that this what it takes to exert authority over a near ungovernable area. It falls to Stéphane, an outsider who is more used to policing in the less unruly parts of France to be disgusted by how far they go. This film also casts a wider net by not focusing on the individual delinquent youths but instead looking at the big picture. Here we see that the police keep an eye on the area at least partially by getting the cooperation of local community leaders like the Mayor, Salah, who leads the more pious Muslims, and even local gangsters and drug dealers. Then of course there are the gypsies to consider and the fact that these local leaders also regard one another as rivals. It makes for a rich tapestry that could only have been made by someone intimately familiar with the local politics.

The revolution when it arrives is much less realistic than the setup that precedes it but I suppose it’s meant as a kind of premonitory power fantasy. As every authority figure including both the police and the local community leaders have failed to stand up for the children of the quartier so to speak, it is they themselves who rise up to strike back. The director thankfully is astute enough not to portray this as a kind of victory. Instead it is shown as the terrible but inevitable consequences of the adults inability to solve the longstanding problems in the commune. In this regard, placing this in the backdrop of the French World Cup victory and the accompanying celebrations makes for especially potent imagery. It is one thing to sing about being united over a sports victory on the streets but the truth is that the miseries of the banlieues continue to exist at least partially because the rest of France do not truly see the mostly dark-skinned people living there as being part of France.

Shortly after watching this we of course see in the news how a video of French police beating up a black man in his own studio has gone viral and has visibly upset the sitting French president. At the same time, France is passing a law to make it illegal to share images of police officers on social media if it is deemed that this could harm them. This more than anything else proves the director’s point and indicates how urgent it is for the rest of France to decide whether or not to the people in the banlieues are French or not after all.