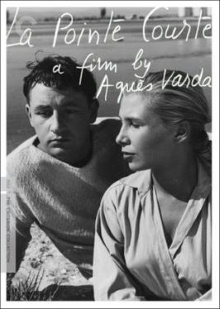

I said earlier that I really ought to watch more films by Agnès Varda and this film only cements that certainty. La Pointe Courte was her directorial debut and some also consider it to be the very first French New Wave film. Most of her films seem to be pretty short and so is this one but it manages to pack in such a wealth of content. On one level it tells the story of a couple who are trying to find their way through their marriage during a trip to the small fishing village but on another level it’s also a kind of documentary about the way of the life of the villagers there. Combined with the exquisite cinematography that she apparently achieved at a very low budget, this is an incredible masterpiece that I think I like more than many of the more well known French New Wave films.

The villagers in Sète are suspicious of a stranger hanging around in town, correctly suspecting him of being a health inspector from the government. They are banned from harvesting shellfish from the nearby lagoon due to bacterial contamination but they secretly do so anyway as they have done for generations. A man who grew up in Sète but now lives in Paris has returned to stay for a few days. He is in the middle of a quarrel with his wife who arrives a bit later. Even as she vents about her frustrations and how she believes that their marriage is over, he takes her around the village. Isolated, poor, and run-down, Sète is no picturesque tourist spot, yet the man shows how he holds affection for it all the same and eventually seems to win the woman over. Meanwhile life in the village with its myriad problems go on: a young man is arrested by the police for illegally fishing but is treated leniently as everyone knows each other, an especially poor family with too many children has one die of illness, the villagers send samples of their shellfish to a laboratory to independently test for contamination and so on.

As the woman observes, Sète is not an easy place to love. From the train station, they trudge through tall and unkept grass to get to the village and beg a boat ride to cross a canal. The poverty is evident in the worn clothes of the villagers and the battered furniture in their homes. There’s nothing romantic in the hard work of fishing and their shellfish really does have bacteria. Yet the man’s deep familiarity with the place fosters appreciation and affection. There’s a stark beauty in the ribbing on the underside of the fishing boats the man’s father used to build, comfort to be found in the routines of the fishermen and during the annual regatta when tourists flood the region, they will dress up for their unique water jousting sport. At the same time, the deep talks that the couple have with one another as they spend time in the village convinces the woman that though the first flush of passion has gone from their relationship, it has been replaced by a deeper, more familial form of love. It is a wonderful confluence of themes that is mature and sophisticated, yet also largely positive, marking it as being very different from the nihilism and cynicism of other French New Wave auteurs.

My least favorite thing about the film is that the man is just so self-assured that the dialogue to his wife seems condescending. It feels like he knows all along how she would feel in the end and is just playing along. Nonetheless there is a surreal quality to the couple having this deeply philosophical conversation as they are on what amounts to a vacation while the villagers around them get on with the ordinary business of trying to get by and this adds immeasurably to the film’s appeal. I do love all of the little stories about the villagers, such as the father being reluctant to let his daughter date while his wife berates him about doing the same thing while wooing them; the adult men railing against the government and even the sad stories like the doctor asking the mother with too many children why she didn’t call him earlier. There is even detail in the background conversations that are only caught obliquely such as the children asking for a particular cat not to be drowned because they want to keep it. The concrete sense of this being a real, specific place is overwhelming.

Apparently Varda decided to make this film while visiting Sète for other reasons and when she did decide to make it, had so little money that she couldn’t pay anyone. It is therefore quite incredible that a film made so hastily as her debut would end up being such a masterpiece. In discussions of the French New Wave movement, though Varda is often mentioned, she is rarely cited as the most prominent of the auteurs. I believe that this is a grave disservice to her legacy and this film has unexpectedly proven to be one of my favorite films that I’ve watched in a while.