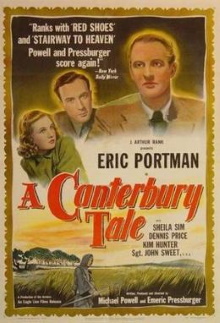

Due to how much I loved The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, I am certainly going to watch more of the work of its two directors Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who as a duo call themselves the Archers. This is again a film that is really about Britishness itself, being inspired by Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, but set during the Second World War. As Chaucer’s collection of stories is about a group of pilgrims travelling to Canterbury, so too is this film about a group of people who befriend each other on the road and find themselves going to Canterbury as well. In this way, it captures a little of what the pilgrimage experience might have been like for those in the Middle Ages and shows off the city and its surroundings to wonderful effect.

American soldier Bob Johnson mistakenly gets off a train at the town of Chillingbourne, thinking that he has arrived at Canterbury. He meets British soldier Peter Gibbs and Allison Smith who has come to work on a farm. While walking together from the train station at night, Allison is attacked by an unseen person who pours glue onto her hair. They later learn that many other girls in town have been attacked by this Glue Man. Bob decides to stay in town an extra day to help solve the mystery and the three soon conclude that the assailant is actually Thomas Colpeper, the respected local magistrate himself. He has a deep interest in the local history of the area, and how the town is a stop on the centuries-old route of pilgrims going to Canterbury, and organizes lectures on the subject to the soldiers. As they befriend each other and get to know the town better, we also learn that Peter is an organist in civil life, that Bob is worried about his girlfriend in the US not writing letters to him and Allison is grieving for her fiancé who was killed in action as a pilot.

I include these plot summaries because they’re helpful to help me remember the films later because but in this case, it’s meaningless because it’s not about the plot at all. It’s just the pretext to get the audience to learn about Canterbury and what the pilgrims in Chaucer’s time might have experienced along their journey. The film even attempts to capture the moment they first came upon the sight of the magnificent cathedral in the distance and then be awed into submission when standing in the shadow of the huge building. At the same time, it’s also about the surrounding scenery, the hills and the woods, and the picturesque streets that date from the Middle Ages, so narrow that two men could reach hands across it, as the villagers put it. We get a look into who these villagers are and how they live too, Allison for example, being a shop girl from London has a harder time getting along with the locals than Bob, who comes from a woodworking family in Oregon. There’s a fantastic scene of Bob joining in with a group of little boys playing, though of course this also reminds us that this is set during a Great Britain at war.

The film adopts a light, pleasant tone and never dwells on the horrors and suffering of the war. Yet its marks are unmistakable and omnipresent, from the need to keep buildings dark out of fear of bombing raids to the destroyed buildings in Canterbury itself and the personal tragedies of the characters. There is an undeniable religious aspect in the film as well, affirming the power of miracles and the majesty of the cathedral itself, yet that is only to be expected given the historical significance of the city. The motivations of the Glue Man are preposterous but there is a grain of truth in it in how the presence of US troops is a mixed blessing for the locals as they are not always the most well-behaved of guests. More than anything else, the film conveys a love for Canterbury and its surroundings as well as a deep appreciation of its role in history and religion. The surest sign of its success is that it makes you want to visit the city for yourself and indeed after its release, there is now an annual festival to tour the locations shown in it.

One unfortunate scene in the film involves the characters making fun of the stuttering village idiot. Such a scene would not be acceptable in a modern scene, and rightly so. Yet this too may be something of an in-joke as the actor who plays the village idiot is also the narrator who reads the extract from Chaucer at the beginning. In all other respects, this is a wonderful film that could only have been made by directors who were motivated by a genuine love of Canterbury and understand what the indefinable quality of Englishness means.