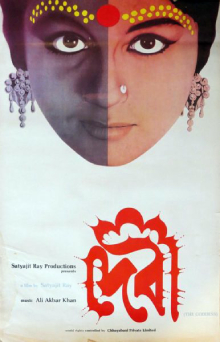

Every one of Satyajit Ray’s films we’ve seen so far has been at the very least strong contenders and this one impresses us once again as a powerful invective against traditional superstition. I particularly love how this film very small and yet very large at the same time. It’s based on a short story and limits its scenes entirely to one family and their household. Yet its themes encompass the pantheon of Hindu deities and carry all of the weight of tradition, the patriarchy and wealth. It says so much and so powerfully in one compact package.

Umaprasad is deeply in love with his wife Doyamoyee but has to leave her at home to complete his studies in English. She is also well liked by the small son, Khoka, of Umaprasad’s elder brother who lives in the same house and the father of the two brothers, Kalikinkar Choudhuri. A wealthy man, he is a devout follower of the goddess Kali and constantly gives thanks for having Doyamoyee to take care of him in his old age. One night he has a dream that he is convinced was meant to tell him that Doyamoyee is really the avatar of Kali herself. The next morning, he drops to her feet in worship and imposes changes to her daily routine and lifestyle. The others are shocked and horrified but when forced to choose simply go along including Umaprasad’s elder brother, who fears being cut off from his father’s wealth if he disobeys. Doyamoyee herself is confused and being only 17 years old, doesn’t know what to think and is fearful of going against the family patriarch. One day a beggar comes bringing his sick grandson and asks that she heal him. Kalikinkar declares that no medicine is more powerful than water that was used to wash the goddess’ feet and allows him to proceed.

This is a rather short film but packs in quite a lot. In addition to the patriarch suddenly imposing the worship of his daughter-in-law as a goddess, there’s also how Umaprasad has received a Western education and sees this as superstition. His peers are his friends and teacher in Calcutta with similarly progressive views. He accuses his father of being senile which raises the question of how often mental issues are excused for religious fervor. Others including members of the community go along with Kalikinkar not necessarily because they believe what he says but because he has money and power. Even the priest Kalikinkar hires appears to have some sympathy for Doyamoyee but resigns himself to doing the job he is presumably being paid for. Despite being hailed as a goddess, Doyamoyee is the weakest of them all, being young, inexperienced and uneducated. She has no say over where to live and how her time is spent. Even before her so-called ascension, there is an evident gulf between her and her husband who being English-educated and more worldly, seems to treat her as a beloved pet rather than as an equal. The film’s plot is comparatively simple yet it is rich in social commentary.

The director’s craftsmanship is also impeccable. The opening montage shows how a statue of Kali is made, painted, paraded as an object of worship in a procession and finally thrown into the water after the ceremony. I don’t have to tell you how that serves as a foreshadowing of what happens to Doyamoyee herself. The scene where she is first asked to heal a child is thick with tension as Doyamoyee watches anxiously to see what her fate will be. Yet it isn’t at all obvious which outcome will be better for her. If she fails to heal the child will the crowd turn against her? If she succeeds, does that mean trapping her deeper into a life she didn’t want and didn’t choose for herself? It’s such a powerful scene that captures how there is no way out for her. I also love how music is used here. The beggar that comes to their door to ask for alms sings out his life story and that’s such a succinct yet effective way to introduce the character.

This film isn’t quite an indictment of all religion. Umaprasad’s teacher talks to him about how he had to fight hard against his own father to change religion. But it does solidly target blind idolatry and how traditional power structures keep the country stuck in the past. That must have been a bold message to make in the 1960s and sadly remains relevant in today’s India.