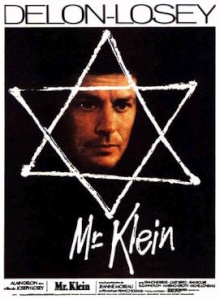

Here’s yet another European film about the Holocaust, especially poignant given current events in Israel. It stars Alain Delon in the title role and more interestingly was directed by an American Joseph Losey after being effectively exiled to Europe after being denounced by the House Un-American Activities Committee. We’ve watched many films that show the concentration camps. This one however is about the bureaucracy that identifies and detains Jews to be sent to the camps and how this warps the entirety of society in Vichy France. Between doubts as to whether or not this Mr. Klein that we see really is a Jew after all and the steadily ratcheting tension as the walls close around the main character, it’s a fantastic film both in its conception and its execution.

In 1942, Robert Klein is a prosperous art dealer who is happy to buy pieces from fleeing Jews at knockdown prices. One day he receives a Jewish newsletter that is addressed to him and discovers that there is another person sharing his name who is a Jew. He ultimately reports this to the police who are suspicious that it is Klein himself who is a Jew and is trying to hide in plain sight. Robert himself becomes increasingly obsessed with finding this other Mr. Klein even as the clues seem to lead him in contradictory directions, to a run-down flat in a slum area where he used to live and to an estate in the countryside where the rich wife seems to have had an affair with him. Meanwhile the authorities pursue their investigation into whether or not Robert is a Jew. He refuses to submit to the indignity of having a doctor physically examine him for Jewish features and instead has his lawyer Pierre obtain the birth certificates of both sets of grandparents. While they wait for the documents to arrive, the police seize his valuables and Pierre asks him to consider taking on a false identity and fleeing the country.

As the preamble states, the character is a composite so the point isn’t really about uncovering some specific truth. The film is deliberately evasive about whether the Robert Klein that we see before us is a Jew. It makes a point of even having his friend and longtime lawyer Pierre ask Robert is his family has any Jewish ancestry he hasn’t disclosed while they are sitting together in baptism ceremony for a relative in a church. While trying to find this other Mr. Klein, Robert experiences all kinds of strange coincidences that are never explained. The landlady in the slums for example remarks that Robert closely resembles this other person who rented the flat from her and he even comes across the other person’s dog who treats him as his rightful owner. Even when it becomes clear that there really is another person, the other Mr. Klein can’t possibly be all these different people from different milieus that Robert always just barely misses. The absurdity of the chase is the point, made to highlight the ridiculousness of the French government’s efforts to identify who the Jews are.

What’s shocking to us in the present is that not a single character in the film objects to the Vichy government’s policies. The most that happens is when a bystander remarks that this is France and surely things won’t come to that. Robert objects to the government mistaking him for the other person who is a Jew but has no issues about them being rounded up. Throughout the film, the police and other agents of the state emphasize that they are only acting in accordance with the law and the lawyer Pierre agrees with them. Even when Robert himself becomes the object of prosecution, he is merely indignant that he, a full-blooded Frenchman of Alsatian ancestry, is still subjected to such treatment. Most films about the Holocaust focus on the camps yet the massive logistical effort they entail would not have been possible without the many levels of civil society being complicit in it. Most of the French don’t think of themselves as being a party in the Holocaust so this film makes for a valuable and powerful corrective.

There are so many other details in the film that are just perfect, Pierre’s wife is constantly in the background and looks on in nonchalance. Robert’s own girlfriend clearly wants only an idle life of leisure and clears out once it’s clear that he is in trouble. There are very few signs that France is still in a state of war and life is good is the countryside estate Robert visits. These serve to heighten the moral failure of a country that sees itself as a beacon of liberty and make this film even more powerful in its condemnation.