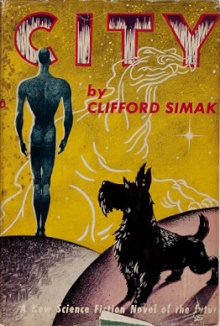

Going through the greatest classics of science-fiction proves to be as rewarding as ever and this one even features dogs! For a person who loves dogs as much as I do, this is very appealing! This book brings together a series of short stories originally published between 1944 and 1951 about a world in which human civilization has fallen and humanity is remembered only by their heirs, the dogs. Each story is accompanied by a foreword that helps connect the whole. The work is very much a product of its time. Author Clifford Simak’s guesses about the implications of technological development feel mistaken to us and the obsession about psionic powers isn’t something that shows up in modern science-fiction any longer. Even so as an exercise of pure imagination to remind us that mankind may not necessarily be the inheritors of some far future Earth, I’d rate this as a masterful and emotionally affecting work.

This book presents the stories in chronological order instead of their original publishing order. As such we start with a story in which there are no dogs at all and end with one in which there are no humans at all. The inter-story notes are written from the perspective of dog historians who wonder if humans ever really existed and that these stories are merely creation myths. The decline of human civilization is progressively documented beginning with the death of cities, a concept which the dogs find unimaginable. The reasoning is that with cheap atomic energy powering flying cars, the ubiquity of robots to provide labor and unlimited food from hydroponic farms, humanity is spreading out across the land to live in expansive homesteads. The cities are emptying out and entire neighborhoods are left to rot. This prediction is wrong of course even if we had such technology today but it does have its own logic. The following stories show humanity becoming ever more attached to their own homes, isolating them from each other and developing talking dogs to be their companions. They are also caught off guard by the appearance of mutants, who look humans but have psionic powers and have no regard for other humans whatsoever. Many centuries pass in between each story but they return again and again to the descendants of a single family, the Websters, and the loyal robot Jenkins who watch over them and later their dogs.

Using Jenkins as the recurring point of view character feels like a cheat and as usual the focus on the single Webster family makes the series obsessively American even as it purports to speak for all of humanity as a whole. It’s a perspective that is staggered across time rather than space or cultural milieus and I have to concede that it does make a fair attempt at imagining how other animals might have nonhuman perspectives on life and existence. I do note that the Websters never seem to consider that the robots might build a civilization of their own and even Jenkins, and the robots he personally supervises, see themselves only ever as being the assistants of humans and dogs. Simak does seem to realize towards the very end of the stories that the robots themselves are another type of civilization entirely with the free robots off doing their own thing. I also like that the fall of human civilization here isn’t due to some catastrophe that humans are unable to overcome. Instead most of them simply move on to a superior form of existence that makes them inhuman while the others become increasingly insular until there aren’t enough of them left to sustain a society. It’s not altogether original but it’s way better than having them die off as a result of some calamity.

There’s a fascinating duality that runs through this series: on the one hand, many of the characters see the change coming and either bemoan the loss of humanity or attempt to take action to avert what they think is a disaster. Jenkins, for example, insists that the Webster house is maintained even when no humans are left and tries to uphold their memory. Yet the stories also imply that humanity is an inherently warlike and violent species so the Earth is better off without them. By the end of the series, even Jenkins is persuaded that every memory of humanity should be purged to allow dog civilization to flourish without external influence. As these stories were first published in the wake of the Second World War, it’s not surprising to see this kind of pessimism about human nature. Of course, having the dogs successfully build a peaceful utopia is pure favoritism and not very plausible but it’s fun and what else is authorial fiat good for. Still, even at the very end if all the animals forget humanity, the robots still remember perfectly so it isn’t quite as tragic as the book makes it out to be.

As a person who loves dogs and generally digs the idea that humanity is not necessarily the end all, be all of civilization on Earth, I enjoyed this book immensely and would recommend it to anyone looking for a not too demanding science-fiction read. That said, while it’s an impressive feat of imagination and ambition, the actual details and the reasoning behind the societal changes aren’t that plausible or realistic. These stories date from the 1940s to the 1950s, when it was normal for science-fiction to include psionic powers. travelling across dimensions by pure force of will, or treating Americans as being representative of humanity as a whole. All these elements have aged badly and no one could ever read this book and consider seriously consider it as a possible future. As such even though this certainly counts as one of the great classics of the genre, its appeal is a bit niche and I can understand why this isn’t better known or more popular.

One thought on “City”