Not long ago, I wrote about how Jafar Panahi’s newer films seem darker than his older ones. Well, I was wrong because I’ve now gone back to watch this and it’s far more depressing. Rather than having a central narrative, this film consists of a series of vignettes about a group of women who are all victims of the Iranian government and society. This is raw and brutal in a way that Panahi’s later aren’t. Even so I detect some amateurishness at this stage of his career, such as the way the camera sometimes focuses on details that are irrelevant.

A group of three young women are trying to gather money to travel to the home village of one of them, Nargess. One is immediately arrested while trying to pawn a gold chain. The two remaining girls continually dodge the police and one of them eventually manages to get some cash from some acquaintances but she loses heart and decides not to go. Nargess goes to the bus station and manages to persuade the seller to sell her a ticket despite her not being accompanied by a male guardian. It emerges that these girls have all just escaped from prison earlier that day. Another one of them is Pari who is hiding out in her father’s house when her brothers arrive, angry that she isn’t in prison and seemingly aim to hurt her. She escapes and goes to a hospital to seek help from a former prisoner. It turns out that she is pregnant and desperately wants an abortion as the father was another prisoner who has since been executed. In this way, this film switches from one protagonist to the next, all of them women who are suffering from the oppression of the Iranian system.

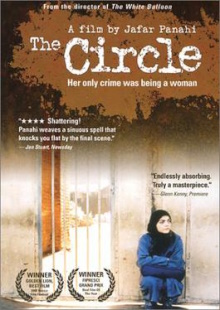

The in media res open leaves the audience wondering just what is going on and it’s quite a while until we realize that these girls are all escaped prisoners. It’s vague as well about their crimes, deliberately so as the film’s tag line is that their real crime is simply being a woman. It’s not for nothing that the very first shot shows how a woman giving birth to a baby girl is treated as a tragedy by her family. At every turn, the various characters skulk and scurry away at the sight of the morality police or raise their chadors over their heads to hide their identities. On their own, they are prevented from freely travelling about, staying in a hotel or accessing medical services. From time to time, we do see happy women as part of the background and of course they are always the ones who are married. This film was naturally banned in Iran but one can still tell that this was made during a time when Panahi thought he could reach a compromise with the authorities. It refrains from showing any of the guards or police officers as being overtly malicious. Instead they’re mostly decent sorts just doing their jobs. Similarly the title already tells you how the film will end and the girls who are criminals do not escape the law, which is usually what the government censors demand of filmmakers. This film wants to blame the system as a whole instead of anyone in particular. It makes for a grim depiction of life in Iran but isn’t as personally bitter as Panahi’s later films.

Strong as it is, the execution still comes across as being somewhat amateurish at times. The street level camera provides a very satisfying look at urban life in Iran, particularly as it emphasizes the grittier and less salubrious parts of the city. However the camera also has a habit of lingering on details that are irrelevant especially given the urgency of the some of the women’s situations. Then there’s how the film tries to isolate each of the characters, sometimes in contrived ways. For example Nargess keeps being asked to wait while her friends goes to ask questions from someone when there’s no good reason why they shouldn’t go together. Even the scene when Nargess sees her home village in a random painting feels too forced. I interpret these issues as Panahi knowing effect he is going for but his techniques aren’t quite refined enough to smoothly pull them off yet. It’s presents a very dystopian view of Iran but it’s also somewhat one note, lacking the wry sense of humor that we would see in the director’s later films.

There are a few things that I didn’t quite get, such as the prevalence of smoking. Is that meant as a symbol of rebellion or of individualism or something else? How exactly did they escape from prison or did were they just given day passes or something? It just feels strange that the police are randomly checking everyone’s papers on the street. This is a powerful film no doubt and so different from the others I’ve watched from Panahi but I think I prefer the richness of the later ones.