It would probably be unwise to take Hayao Miyazaki at his word that this will be his final film and I’m not terribly fond of the quality of his later ones anyhow. Still, it would only be fair to watch at least one of his films properly in the cinema and so here we are. This one does finally feature a boy as the protagonist and apparently that’s because it’s semi-autobiographical. It also starts strongly with a firm grounding in reality but eventually veers off into the most fantastical and dream-like of Miyazaki’s worlds yet. There are all kinds of possible interpretations but none are terribly solid or boldly stated enough and so this is again mostly an exercise in pure imagination.

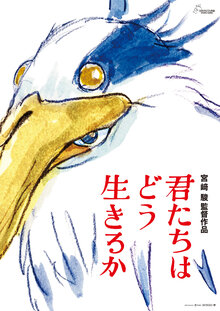

Some time after his mother is killed by a bomb raid during World War 2, 12-year-old Mahito Maki moves with his father from Tokyo to the countryside. His father owns a factory that appears to manufacture fighter aircraft and marries his late wife’s younger sister Natsuko who is already pregnant. Natsuko tries to be a mother to Mahito but he spurns her affections. Near the house is a derelict tower built by Natsuko’s granduncle, said to have been an eccentric genius. Mahito is plagued by an unusually intelligent and aggressive grey heron on the grounds and tries to chase it down using a handmade bow and arrow. When Natsuko falls ill due to morning sickness and subsequently disappears, the elderly maids of the household search for her. Mahito leads one of the maids into the tower, convinced that she is inside. There he finds that the grey heron serves Natsuko’s granduncle, the master of the tower, who still lives. The tower itself seems to be a nexus into many other worlds and eras, with each person having their counterpart. In particular, Mahito meets Himi, a fire-wielding girl, who appears to be some version of his own mother.

Opening with Tokyo being firebombed by the Allies is grim stuff and while Mahito is obviously a boy from a privileged background, the rationing and other constant reminders that the war is still in progress grounds the film. I really liked the early scenes establishing the countryside manor and the grey heron who is annoying to Mahito but not so much that others find it weird. However once Mahito enters the tower, the gloves come off and Miyazaki lets his imagination loose with no restraints whatsoever. At first, it feels like Mahito has entered a kind of parallel spirit world as in previous films, but as his adventures go on, reality becomes ever more malleable, lending the whole experience a surreal, dream-like quality. It’s doubly weird how birds of all types are treated as the antagonists and bird shit is a recurrent motif. It’s Freudian free associations and vague references all the way. I do note that Studio Ghibli seems to have gone back to an older visual style in this iteration and so while this is as visually ambitious as, say, Spirited Away, it has less of an immediate wow factor.

Underneath the weirdness, we can still discern some meaningful themes. What struck me was the simmering resentment and anger inside the character of Mahito, whereas the girl characters in Miyazaki’s films are usually joyful. I believe that this resentment is directed mostly against his own father for obvious reasons. Mahito never displays any affection for his father in this film and any warmth in their relationship in one way only. Given the autographical nature of this story, that alone speaks volumes. There may be other interesting references. Could the aggressive parakeets refer to the fighter aircraft manufactured in the factory owned by Mahito’s father and the Parakeet King himself refer to the Japanese Emperor? I wish Miyazaki could have been bolder in asserting these connections but it seems this is already as bold as he is willing to be. Interesting as these themes are, they are weakened by the inclusion of Miyazaki staples like reincarnating spirits, being a dutiful child, and so on. They’re always present in his films and here only serve to dilute the more novel and original elements.

The Boy and the Heron does mark a notable change from his other films but it doesn’t go far enough. Meanwhile he’s as obsessed as ever with fantastical worlds and sheer flights of fancy. This causes the film to be too long, bloated with empty fluff and dumb gags. I can’t imagine anyone finding the heron character in his human form either likable or even funny. On top of it all, it’s a step back in terms of visual quality from peak Studio Ghibli, making this a subpar work.