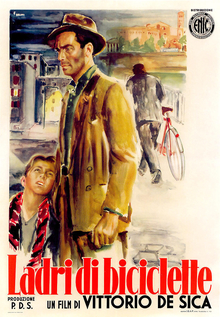

Since this is intermittently hailed as one of the greatest films of all time, not having watched it was one of the most major gaps of my cinematic journey. It’s pretty much as I expected from its reputation, being a powerful tragedy but also one that is too dated for me to really fully appreciate. One thing that did strike a chord with me is how much it’s really about the alienation and isolation of man rather than just how hard life is. The ending isn’t a surprise as the main character Ricci works himself up to it throughout his search, ignoring alternative solutions and other people in his obsession to retrieve his bicycle. I suppose this sort of depth is why it’s such a highly regarded film.

Antonio Ricci is one among countless others suffering amidst the economic depression in post-World War 2 Rome. One day the city’s employment office offers him a job posting advertising bills on condition that he owns a bicycle. He accepts the job even though he has already pawned his bicycle to buy food. His wife Maria strips their bed for the sheets, reasoning that they can sleep on bare beds, to pawn them to get the bicycle back. His older son Bruno seems to work in a petrol station and he has another younger infant son. On his very first day of work however while he is on a ladder, his bicycle is stolen by a youth. He attempts to chase the boy now but is led off the track by accomplices. He reports the theft to the police but is told that there is nothing they can do. His friends tell him that the bicycle will probably be dismantled into parts and resold at the Piazza Vittorio market. When he goes there the next day, he is dismayed to see so many bicycles and the associated parts for sale that it is impossible to tell which one might be his.

This film is old enough that I’m not altogether certain if what I’m reading into it accords with director Vittorio De Sica’s intentions. In particular the sympathy that the audience is supposed to feel for Ricci and his family is obvious, especially as he is always accompanied by his plucky young son. Yet I also detect some negative judgment against him. As the fortune teller seems to hint, once the bicycle is gone, it’s gone. In his single-minded quest to get it back, Ricci ends up neglecting other concerns, including Bruno’s safety. It’s interesting to me that the film leaves the audience in no doubt whatsoever who the thief is. Yet Ricci fails to get his bicycle back largely because the thief is backed by an entire support network of family members, friends and even neighbors. On the one hand, this is a condemnation of the dire state of society that even blatant criminals have the support of their local community. Yet I also can’t help but notice that Ricci seems to neglect his own friends and family. He demands assistance and is never humble in his desperation to get back what belongs to him. For example, he causes a nuisance in a church service to force an old man to give him information instead of throwing himself on the mercy of the institution’s charitable efforts. The effect is that Ricci progressively loses the audience’s sympathy, setting the character up for the climax.

I know too little about the state of society in Italy immediately after the war to offer meaningful commentary. I found it fascinating that while it depicts widespread poverty and misery in the streets of Rome, it also goes out of its way to show that there are also pockets of prosperity. The rich family with the smirking son Ricci and Bruno see in a restaurant is a case in point. The economy is under stress yet civil society is clearly still functioning as the police continue to operate and the middle classes continue to enjoy football matches and theatrical plays. To me, it’s of course a tragedy that a working class man is pushed to such desperate straits, yet this is a film about the human spirit being put to the test and failing. As others have pointed out, even from the very beginning of the film, Ricci is a man who has already lost hope. The sudden job opening brightens his spirits temporarily but they are quickly snuffed out again. Even his friends seem somewhat skeptical about the odds of finding his bicycle again. That’s why I found it difficult to like the character much even right from the start.

This is a great film, of that I have no doubt, but it isn’t one that I particularly like. What passes as realistic for the Neo-Realism movement at the time doesn’t feel particularly realistic nowadays. It even rather cheats by having Bruno be such a cute and likable boy to contrast against the desperate and simple-minded Ricci. I also dislike how his wife Maria has so little role in the story. She’s decisive enough to offer her bedsheets to be pawned but later Ricci hides the loss of the bicycle from her such that she has no subsequent role in solving the problem. Perhaps that is in keeping with the need for the man to be the provider of the family, shielding his wife from problems like this, but it makes him even more unlikable to me.