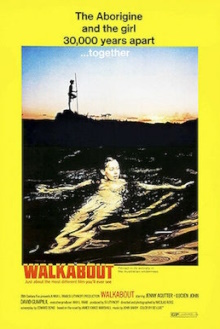

This is commonly cited as one of the great Australian films even if there is some debate over whether it counts as being Australian at all. Director Nicolas Roeg and the two white actors are English. I’d say it easily counts as this is probably the definitive film about the Outback. I’m not a big fan of this use of the noble savage trope and I found its core message to be similarly outdated and simplistic. Even so I can appreciate how perfectly this film conveys that message with its vivid, almost hallucinogenic vision of the Outback and its boldness in using nudity and sheer physicality for both the male and female characters.

An English man living in Australia drives his two children, a teenaged girl and a young boy, deep into the Outback, supposedly for a picnic. There he pulls out a gun and starts shooting at them. The boy thinks it is a game but the girl realizes what is going on and carries him to safety. Then the father sets fire to the car and shoots himself. She conceals the suicide from her brother and gathering the food from the picnic, sets out with him across the wilderness. The food soon runs out and by the next day the boy is too exhausted to move and must be carried. They finally make it to an oasis with a fruit tree and are seemingly saved but are confused when the pool dries up overnight. Just then a nearly naked teenaged Aboriginal boy comes across the two. Despite being unable to communicate, the boy cheerfully teaches them how to draw water from the bed of the oasis and hunts to get food for them. As they travel together, the brother learns to communicate with the Aboriginal boy but the sister remains distant and wary.

This was a controversial film at the time due to the then teenaged Jenny Agutter having fully naked scenes as the sister and the inclusion of very graphic shots of animals being slaughtered. The camera clearly sexualizes both the sister and the Aboriginal boy as well which at times makes this film uncomfortably salacious. Yet this is indeed part of Roeg’s vision. He is very explicit in evoking the Biblical Garden of Eden, with imagery of slithering snakes and the profusion of life amidst a seemingly hostile landscape. Nudity then represents a return to a state of innocence and sexuality too is part of it as the Aboriginal boy’s dance at the end is a courtship ritual. The psychedelic quick-cuts jumping to other times, people and places add to the symbolism and emphasize that the journey of the sister and brother across the Australian Outback is as much a spiritual one as a physical one. This is certainly an artistic triumph and a bold statement.

An easy observation to make is that neither of the two white siblings react believably to the murder attempt by their father and being faced with almost certain death themselves. The sister has almost zero emotional affect even as she witnesses the Aboriginal boy butcher kangaroos for meat nor does she wonder at her father’s motives. The brother complains at first at being made to walk so much but seems perfectly content once they are in the company of the Aboriginal boy. The point is that none of them are characters in of themselves but rather represent their respective civilizations and ideals. Note how none of them are ever named. Nor does the film explain the father’s actions at the beginning. It doesn’t need to, as we can infer for ourselves that it is due to the pressures of living in a modern, competitive society. I can’t fault the intensity and purity of the clash of civilizations as presented here but it goes without saying that it’s simplistic. As the film itself suggests, it’s easy to depict the trio’s sojourn in the Outback as being idyllic when it’s just the three of them, but if you were to place the Aboriginal boy back within the context of his own people, it’s not so obvious that they would be living in paradise.

So this is a case in which I can readily acknowledge the greatness of the film, the power of its vision, its cinematography and artistic boldness, while broadly disagreeing with what it wants to say. Still I have no doubt that this is a message that resonates with many and it is fair to consider this as part of the Australian national identity.