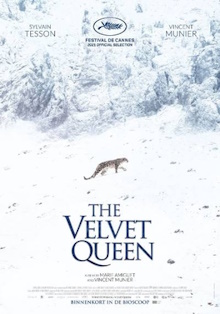

Nature documentaries are always spectacular and easy to watch. This one however does choose to do things a little differently. While the subject is the search for elusive snow leopard in the Tibetan highlands, it also puts two of the filmmakers, wildlife photographer Vincent Munier and writer Sylvain Tesson, in front of the camera instead of behind it. So in conjunction with the breathtaking shots of the landscape and the animals, there’s also extensive commentary by the two as they reflect on the beauty of what they see and lament how spiritually impoverished the modern world feels in comparison. It’s a nice idea but I don’t think it worked very well as their observations are simply not that original.

The film presents itself as the result of a fortuitous encounter between Tesson and Munier as the latter invites the former to join him on his quest to document the Tibetan snow leopard in person. Though well-travelled, Tesson is visibly less experienced to such harsh conditions and Munier has to caution him, among other things, about making too much noise as they hike in order not to scare the wildlife away. Along the way they capture plenty of arresting imagery of both the landscape and the animals. It’s no huge spoiler to reveal that they do eventually manage to catch sight of the legendary snow leopard but in true dramatic fashion, it happens only near the end of their journey. Before that, they content themselves with spotting plenty of other wildlife so there’s always plenty of excitement. They also meet and interact with the local population and it’s interesting to note that there are people living in relatively close proximity in these areas. Through it all, they philosophize to each other as the French are prone to do. Munier comments on how he is most at home in the wilderness while Tesson agonizes over the extreme hardship and patience that is required for a chance to catch a glimpse of their elusive prey with no guarantees about success.

This approach effectively turns the duo into the subject of the film as much as the environment around them and the wildlife they encounter. It’s unusual and a little dishonest in my opinion as there is obviously more than just the two of them on the trip as someone needs to be carrying the camera and pointing it at them. Yet whoever it is is never shown and never participates in the conversation. Another issue is that the narration uses very poetic and philosophical language but doesn’t have the originality and depth to match. There is no need for us to hear them exclaim to each other how sublime the view is. Just show us the footage and let us see for ourselves. Similarly Munier may be perfectly earnest in stating that he so loves nature that he doesn’t know how to function normally in civilized society. Yet we can also see for ourselves that he holds the privileged position of being able to straddle both worlds and make a decent living doing so. We don’t see him giving up his wildlife photographer career to live as a Tibetan herder for example. As other critics have noted, this sort of moralizing often comes across as being distracting and unnecessary.

The imagery is unquestionably beautiful however and one thing that this style of documentary filmmaking allows is showing the animals’ reactions to their presence. As much as they attempt to be stealthy and wear a layer of camouflage, the senses of the animals are far better attuned to the environment. So even as they take videos and photographs of the bharals, the rodents, the mice and other wildlife, the animals look back at them. Tesson actually becomes concerned when the larger animals take notice of them and move towards them. It’s powerful reminder that humans in the midst of nature can never be passive observers. They influence the land and the animals who live in it by their presence and they alter their behavior and react in response. I also liked having Munier point things out to Tesson, to look for the silhouettes of the animals against the ridges for example, or fossilized tracks and clumps of fur left on the rocks. It’s a simple but effective demonstration of the former’s expertise and experience.

On one level, I have to concede that Munier’s well of knowledge grants him the authority to comment on what all this means to him. Yet it still grates me how shallow and clichéd his observations are. Being a writer, Tesson’s remarks, such as his plea to embrace poetic meaning, are more interesting. Even so, I’d prefer to do without such commentary unless they were truly original and let the images speak for themselves. The style here is definitely different from the usual BBC documentaries that we watch but I think I prefer the BBC house style.