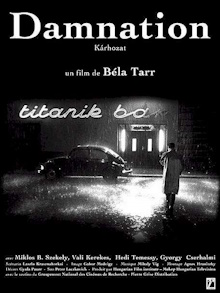

After the incredible yet grueling experience of watching Sátántangó, it’s about time we moved on to more of the work of Béla Tarr. This is a more normal two hours long but it’s still similar in many ways with its rain-soaked remote mining town, dreary atmosphere and horrible people. The black and white imagery is exquisite and the vibes I got from it reminded me at times of the work of David Lynch. Unfortunately I found it to be far too overwrought and the self-flagellating speech in it so tortured that it would have been better to omit it entirely.

Karrer, a depressed man who seems stuck in a mining town, is obsessed by a torch singer who performs in the local bar. The owner of the bar Willarsky offers him a job that entails travelling abroad in order to smuggle back a package that is implied to be illegal. He refuses, claiming that he can never leave the town, and recommends the singer’s husband for the job instead. While the husband is gone, Karrer aggressively pursues the singer, repeatedly professing his love and when she refuses him, gets physically abusive. She eventually gives in and has sex with him when he pathetically denigrates himself. Afterwards she simply reminds him that her husband will be back the next day. Through it all, we hear him deliver existentialist monologues in a drunken state to whoever is willing to listen about getting old, about having reached his limits and about the pointlessness of striving, amidst the ever-present backdrop of the cable lines ferrying loads of coal.

If nothing else, this is a masterpiece of composition as every frame is visually arresting. It’s all post-Soviet industrial squalor, muck and dirt, but it sure looks beautiful. Tarr likes to slowly pan the camera across the scene or zoom in and out to capture details at different scales. This gives the impression that it is the world Karrer inhabits that is the real subject of the film rather than the man himself. Indeed he is content to let the camera roll on long after the human subjects have walked out of a shot. There’s a languid, dream-like quality and the scene in which the torch singer is performing feels exactly like something by David Lynch, down to the musical choices. At times, this even feels too static to me. The shots are composed with such exacting care that the performers are required to hold still or move very slowly as if they were in a photograph. Even near the end, when there is a large dance party scene, there is very little energy in the film but I suppose the very petrification of the town and everyone in it is part of the theme.

Unfortunately having already watched Sátántangó, this feels like more of the same in a less refined form. I’m particularly annoyed by Karrer monologues. I doubt that the actor even fully understands the lines that he is delivering and the people who are forced to listen to him have a hard time keeping a straight face. My favorite response is that of Willarsky who basically tells him to quit his self-pitying bullshit as everyone has their own problems. Indeed as the title of the film indicates, it is Karrer who is damned. His profound, philosophic musings are an empty mask for his depression, lack of inner drive, and even lust. I’m not sure that Tarr would agree with me but I found Willarsky to be a more uplifting. Sure, he’s a lawbreaking capitalist, but he’s actively doing something about improving his lot in life and get himself out of this empty backwater. This too is precisely what the singer wants for herself and is she wrong for it?

I can’t deny what an an incredible piece of craftsmanship this film is but it seems to me that Tarr’s magnum opus is Sátántangó and this is just a sort of trial run in comparison. Furthermore, the more Karrer speaks, the dumber this film feels to me so I’d prefer almost no dialogue and let the visuals speak for themselves which is what Tarr is best at anyway.