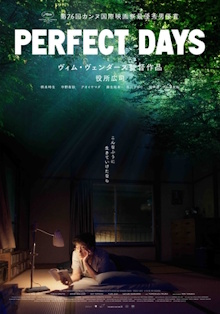

We really should be watching more of the work of Wim Wenders and this tight package that is almost as perfect as the days it portrays is a good reason why. It’s such a neat confluence of exactly the elements that we tend to like in cinema: very sparse dialogue that relies on visual storytelling, a protagonist working a mundane job with a rich, inner life, and a positive attitude towards life. It does cheat a little I feel as I doubt that the daily routines of a real-life toilet cleaner even in Japan is this stress-free and Wenders’ musical picks alone carry so much emotion, but this really is one of the best films I’ve watched this year.

A man who is getting on in years, Hirayama lives by himself in a small apartment in Tokyo and works as a toilet cleaner. His everyday life consists of the same fixed routine: waking up, watering his plants, buying coffee from a vending machine, going about his rounds in his minivan while listening to cassettes of 1960s and 1970s music and so on. He has no close friends and rarely speaks even to his younger colleague, Takashi. Despite this, he seems perfectly contented with his life, greeting the sun every morning with a smile, enjoying his glasses of iced water and a soak in the public baths after work. On his days off, he does chores like getting his laundry done, cleans his flat, shops for a new book to read and spends time in a small restaurant where he is friendly with the proprietress. His routine is disrupted one evening when he returns home to find a young woman waiting for him. It turns out to be Niko, his niece who has run away from his sister who he has not seen in many years. He gamely lets her stay with him and takes her along to work.

This feels like something that was tailor-made to our cinematic preferences and it’s not a coincidence that it’s reminiscent of Paterson, a film which we similarly loved. It’s a celebration of the mundanity in life, an assertion that an existence that consists of nothing more than a comfortable routine repeated day after day can still be a meaningful and happy one. Perfect Days does go a little further as most people would consider Hirayama’s life to be a profoundly lonely one. Takashi notes that he barely knows Hirayama’s voice and probably the most conversation he has is when the book seller offers him some commentary about his choice every week. He does delight in all sorts of indirect interactions, like playing Tic-Tac-Toe on a piece of paper he finds in a toilet with a random stranger or nod politely to the other regulars at the baths or the restaurants. Yet if that level of social engagement is enough for him, who are we to say otherwise? The film drops hints of tumultuous events in his past without providing specific details and certainly he is old enough to have had a storied life. So it’s fine that this is how he has achieved peace and balance.

Even in as orderly and hygiene-obsessed a country as Japan, Hirayama probably achieves his so-called perfect too easily. His beat is of course the Shibuya district, one of the most expensive places in Tokyo, and it’s quite impressive that he can afford a single-person apartment and a mini-van on a toilet cleaner’s salary. At one point, Takashi resigns suddenly leaving Hirayama to do all of the work by himself, ruining his day. In the film, it’s depicted as just one bad day, but I’d bet in real life, there are more days like that than hassle-free, uneventful ones. It’s amusing that the film depicts Hirayama’s mini-van smoothly cruising along the highway to musical accompaniment while the lanes in the opposite direction are jammed. Perhaps we could interpret this as meaning that contentment and relative happiness are more a matter of a state of mind than the specific details of Hirayama’s routine. Certainly this is a triumph of the thisness of experiencing life as he is depicted as being always mindful of every detail of the environment around him, being precisely the type of person who stops to smell the roses so to speak.

As I noted when writing my thoughts about Paterson, this sort of complacent, unambitious life is largely how we live ourselves so it’s not surprising that this is the sort of film that appeals to us very much. I’m also tickled pink about being able to recognize the highways of Tokyo from my time spent on the Shutoko Revival Project. This sort of lifestyle isn’t for everyone and there are limits to how seriously we ought to take so idyllic a vision as this, but it is an excellent one and I’d love to see more work like this.